New Dietary Guidelines Expected to Group Seed Oils With Ultra-Processed Food. That Alone Is a Breakthrough.

By Cate Shanahan, MD, Special to The MAHA Report

A rumor is circulating that the soon-to-be-released U.S. Dietary Guidelines may, for the first time, explicitly acknowledge that industrially refined seed oils are highly processed and potentially problematic. While the final language has not yet been released, even a modest shift in this direction would mark a meaningful departure from decades of guidance that treats these oils as an unqualified nutritional upgrade, particularly when compared to foods like butter and tallow.

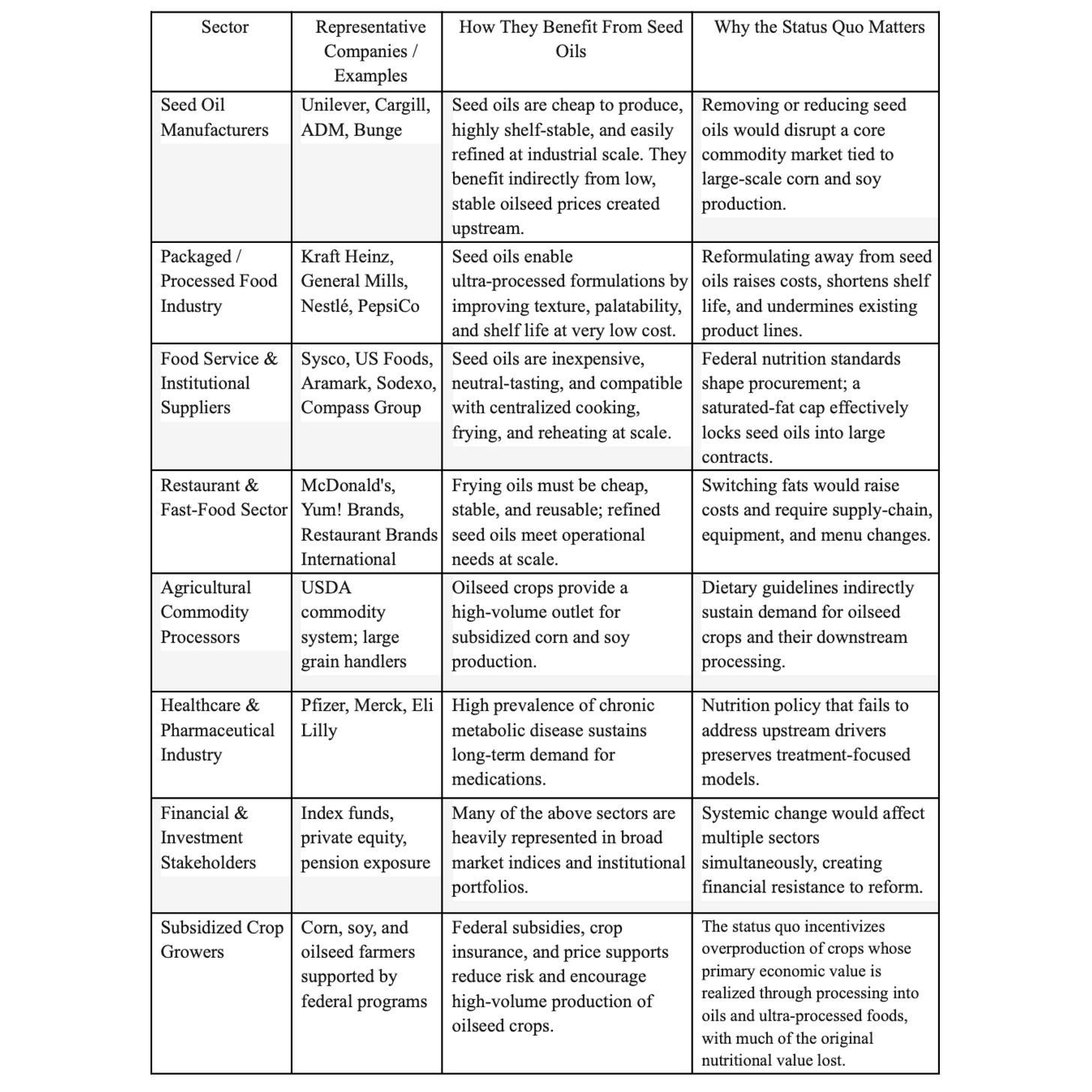

Such a change will not have come easily. Seed oils are deeply embedded in the modern food system for almost non-negotiable reasons. First, they’re amenable to mechanized farming, and a shift back towards traditional animal fats would necessitate restructuring our agricultural system on a grand scale. Second, they’re vital to the economics of processed food, fast food, and most commercial food establishments due to how cheap they are. Enormous financial interests are tied to their continued dominance.

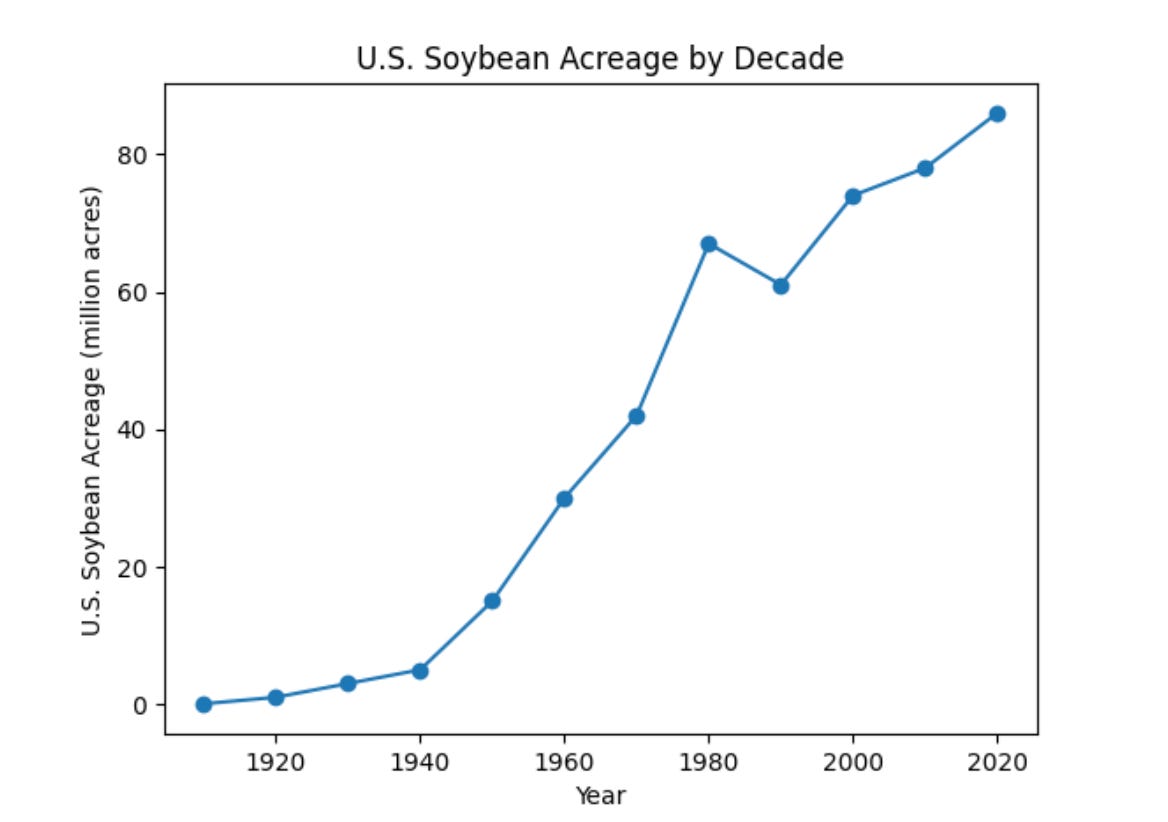

[Data for the above image comes from https://www.soyinfocenter.com]

To understand why even tentative recognition of seed oils as problematic has been so difficult to achieve, it helps to start with scale. The first chart, below,shows how the amount of U.S. acreage devoted to growing soybeans (the predominant seed oil in our food supply) exploded during the 20th century, from a marginal crop a century ago to one of the dominant uses of U.S. farmland today. This reveals just how novel the oil is in the human diet, as soybeans were a minor crop in the United States prior to the 20th century.

Soybeans have slowly reshaped our entire food production system. First, by serving as a source of industrial engine lubrication for Henry Ford’s automotive industry; later, for the planes, tanks, and guns during WWII. Following the war, soy oil was replaced by petroleum. But we kept growing soy because farmers had started using soymeal to fatten animals faster than grass could do. Today soy meal is also used as a meat extender, or replacement, in numerous processed foods. There was really no market for soy oil, until the American Heart Association started recommending it as a cholesterol-lowering agent. [Discussed in a previous article--maybe you can link to?] Thanks in part to their continuing ideology that cholesterol is harmful, we now eat far more soy oil than we do butter, lard, tallow, and all other animal fats combined.

I do not know if the guidelines will define seed oils the same way I do. So, at this point, I want to clarify that there are eight refined seed oils that I’m concerned about: Corn, canola, cottonseed, soy, sunflower, safflower, rice-bran, and grapeseed. (See my previous article for The MAHA Report, here). I borrowed from Quentin Tarantino to coin a catchy term for this collection of problematic oils: The hateful eight.

If you’re not already aware of why they might be harmful, I encourage you to visit my website. You can freely read articles telling the story of how scientists used poorly designed studies to convince a trusting generation of dietitians and doctors that saturated fats caused heart attacks, and seed oils prevented them. I also discuss links between seed oils and oxidative stress that dietitians, and MDs like myself, do not learn about during our training.

How Previous USDA Guidelines Have Quietly Forced Americans To Eat Seed Oil

While you may not look to the USDA Dietary Guidelines for personal nutrition advice, what they recommend still matters to you—and your family.

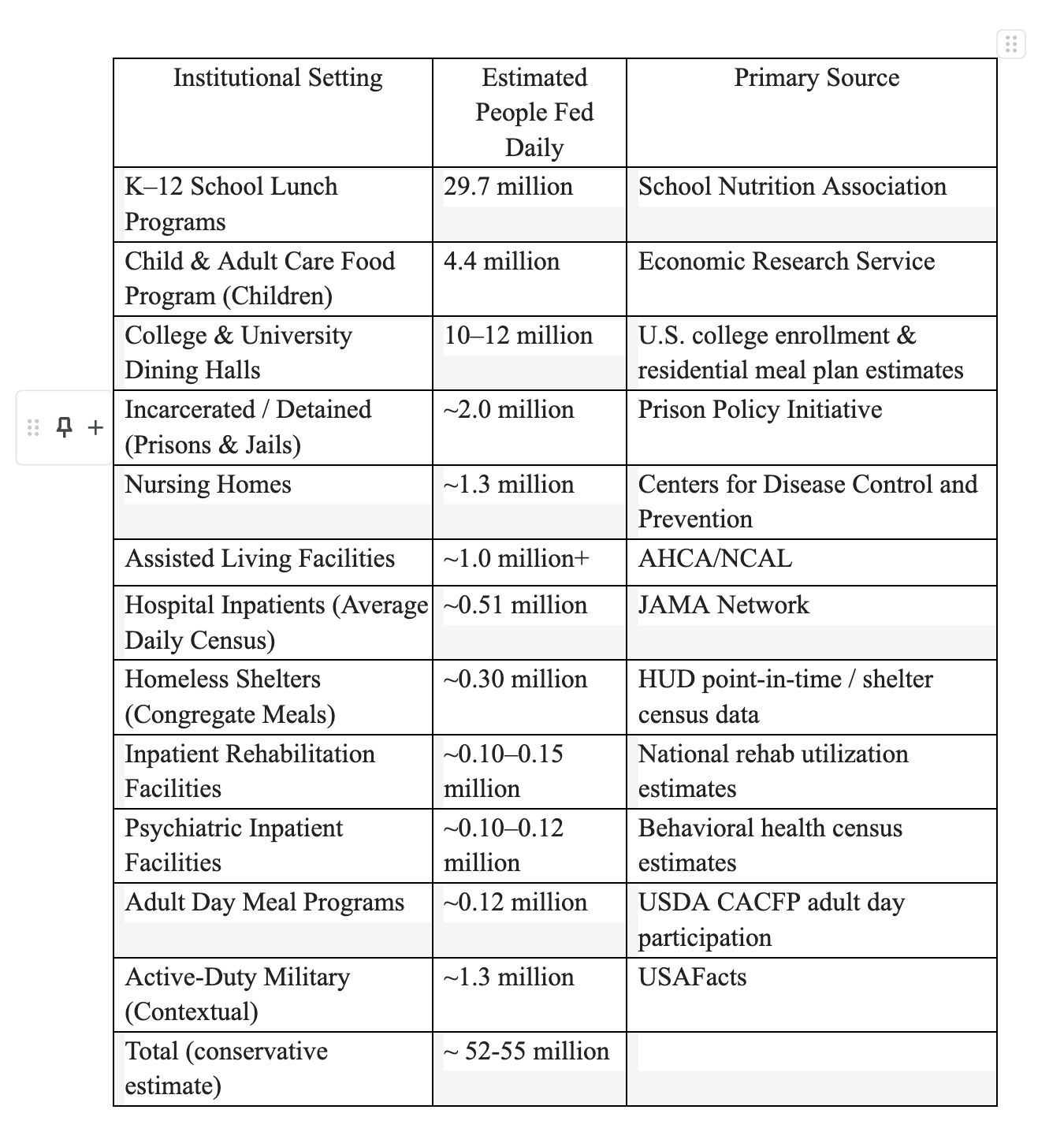

Most seed oil consumption occurs without anyone’s awareness, through packaged foods, restaurant meals, and institutional meals. And a good portion of that consumption is essentially mandated by law. You see, USDA guidelines set the defaults for federal food programs, schools, universities, hospitals, long-term care facilities, correctional institutions, and other environments where people eat what is served to them, not what they select from a grocery shelf. Even individuals who go out of their way to avoid seed oils in their own homes remain affected by these standards the minute they step outside to grab a bite to eat.

The second chart estimates just how many people are exposed to seed oils daily in settings where choice is limited because federal guidance directly determines what ends up on the plate. The total estimated captive market is upwards of 50 million. As you can see in chart 2, below, using processed seed oils to make processed foods has been quite a good business model.

Chart #2

And remember, we’re not even talking about the fact that seed oils have replaced olive oil, tallow, lard and peanut oil in restaurants, take out, and convenience foods. The total number of people exposed to seed oils daily, often without realizing it, is much higher than 50 million.

Could Refined Seed Oils Be Changing What It Means to Be An American?

Better data is sorely needed.

If you personally avoid seed oil, you may be tempted to think that it’s hardly worth the trouble of fighting huge systems because you’re personally doing just fine. That may be so, for you as an individual. However, we are not islands. We are members of a society. And our society is increasingly disrupted by the burden of sickness. As healthcare systems allocate more resources toward treating chronic illness, fewer resources remain available for acute and emergent care. In practical terms, this means higher costs for everyone, increasing strain on the medical workforce, and reduced availability of timely emergency services—even for those whose own diets are otherwise careful. By calling out seed oils, the new USDA guidance will at least enable us to ask these sorts of questions.

And the first step towards making meaningful evidence-based connections between massive changes to our food supply and massive declines in our health as a Nation is better data.

You see, in spite of its ubiquity in the food supply, the government does not track our seed oil consumption. This allows certain academics to claim that we do not eat enough, and then urge us to increase our consumption.

However, independent researchers who estimate our true intake from the only data available have discovered that we eat quite a lot. Along the lines of what you might expect, after looking at the remarkable increase in production shown in my first graph, our consumption has increased 1000 fold between 1909 and 1999. As of 1999, roughly 10–15% of calories were coming from refined seed oils.

Importantly, since 2000 our consumption may have risen significantly higher. In the absence of reliable publications, I’ve compiled my own data using Statista and related sources. I suggest that figure is now closer to 20-30%. In other words, our intake has doubled in the past 20 years.

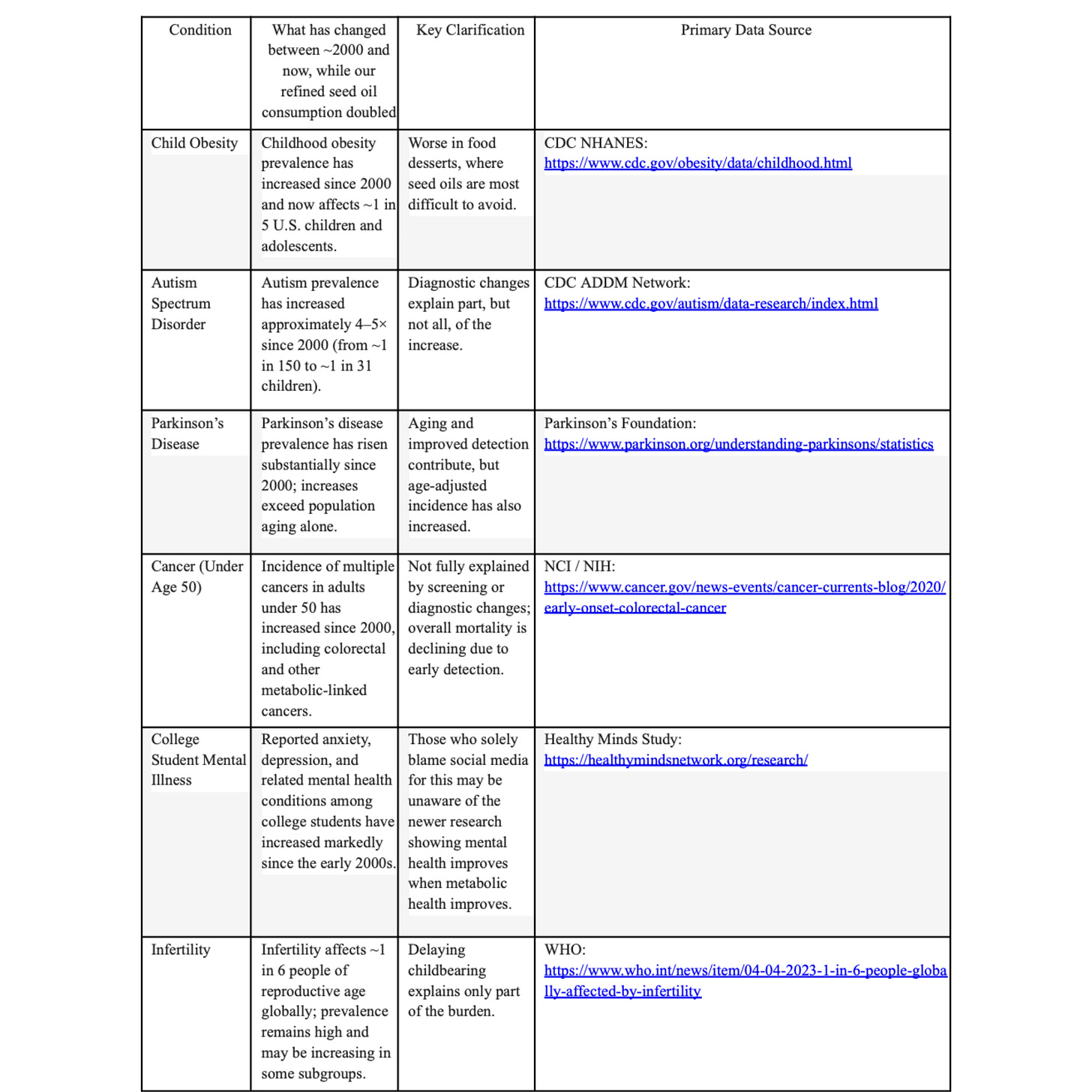

Now let’s look at the changes to just a few of the most well tracked chronic health conditions during that time. I want to focus on that time period because, as shown in Figure 1 of this publication, other key drivers of metabolic health have been relatively stable in that time period (sugar, flour, red meat), and seed oil is an outlier variable that deserves to be studied far more than it has been.

The new guidelines will, quite likely, lead to better data. Better data will help to raise awareness of the very concerning correlations between seed oil consumption and serious illnesses, including many affecting the brain, as listed in Chart 3. Nutrition scientists have been denied the tools and the permission to study seed oils independently because of previous assumptions about their health effects. This is partly why few people have even looked for the correlation I’m describing, and it’s a necessary first step to identifying potential causative links.

Chart #3

Among the most promising causal mechanisms that I’ve been studying are the oxidation products that develop in seed oils, particularly toxic aldehydes. It’s well established that toxic aldehydes in our diets can disrupt mitochondrial function, promote inflammation, and destroy cell membrane integrity. Unfortunately, most dietitians today are not taught that foods made with refined seed oils contain varying amounts of toxic aldehydes, and as a result, deny they exist. This disconnect needs to change. But there are many barriers standing in the way. Those barriers include some of our most powerful industries, listed on chart 4.

chart #4

Our future depends on strategy.

Our culture is addicted to cheap calories, and these industrial seed oils are not isolated ingredients that can be swapped out without consequences. They are embedded across agriculture, manufacturing, institutional procurement, and clinical guidance. Entire supply chains—farms, farm equipment, fertilizers, university agricultural departments, oil refineries, packaged food formulators, foodservice distributors and institutional kitchens—depend on refined seed oils.

That is why this issue is so resistant to change. A policy shift that meaningfully highlights the need for more rigorous research on seed oils is not a superficial messaging change. It alters what questions are considered legitimate to ask, which determines what hypotheses earn funding. And that’s been a real problem for science itself. I’ve spoken to a number of respected researchers who’ve told me they face constant challenges doing the work they do because the people who decide what grants get funded assume the issue is already settled, and their grant requests get denied.

Explicitly recognizing the ‘hateful eight’ seed oils as highly processed and potentially problematic creates space for proper investigation into their biological effects. If we want to move the needle on chronic disease, we have to move the needle on a nutrition narrative that has a 40-year-plus track record of failure.

Highlighting seed oils as a group that deserves further study is foundational to making positive change. It lifts the structural constraints that have prevented scientists from paying much attention to these oils, and makes much needed change possible.

That is why this moment matters. Not because one policy may or may not change this year, but because it makes clear that progress on chronic disease will require a new research strategy, not just new statistics based on the old nutrition ideology.

Dr. Cate Shanahan, MD (DrCate.com), is The New York Times bestselling author of Deep Nutrition, Food Rules, The Fatburn Fix, and, most recently, Dark Calories. You can subscribe to her free newsletter here.

I hope that I can safely continue using unrefined organic sunflower and grapeseed oils if only as ingredients in some baked items. I'm glad this article added the word "refined". I get so confused when everyone just says "seed oils" without mentioning its the refining that turns them bad.

Flour has changed though with the addition of *enrichment* with the worst offender being folic acid as a form of B9. It is basically poison for about half the population and leads to autism characteristics in many people. It needs to be removed from all foods.