Almost everyone knows that the food pyramid, that 1992 graphic that remains our most iconic diet image, has been discredited as nutrition advice. But fewer Americans are aware that it’s still with us, incredibly, as the basis of government information on diet—and that this still matters.

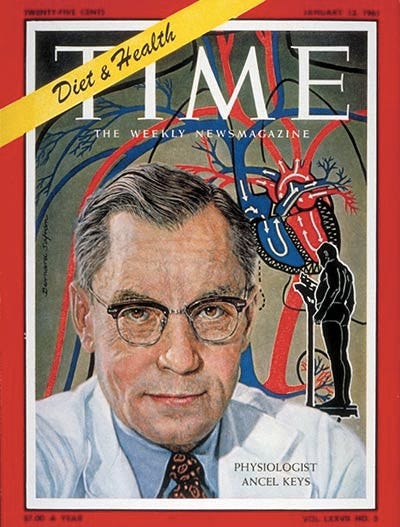

The story of the pyramid’s origins and its enduring clout starts with some weak science performed by an ambitious physiologist, Time Magazine’s 1961 man-of-the-year, Ancel Keys, then continues as a tale of longstanding bias, industry influence, ideology and politics. All this must change if President Trump and Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. are to deliver on their promise to reverse chronic disease in America within two years. Reputable science suggests that goal is possible, but we need to understand how we got here.

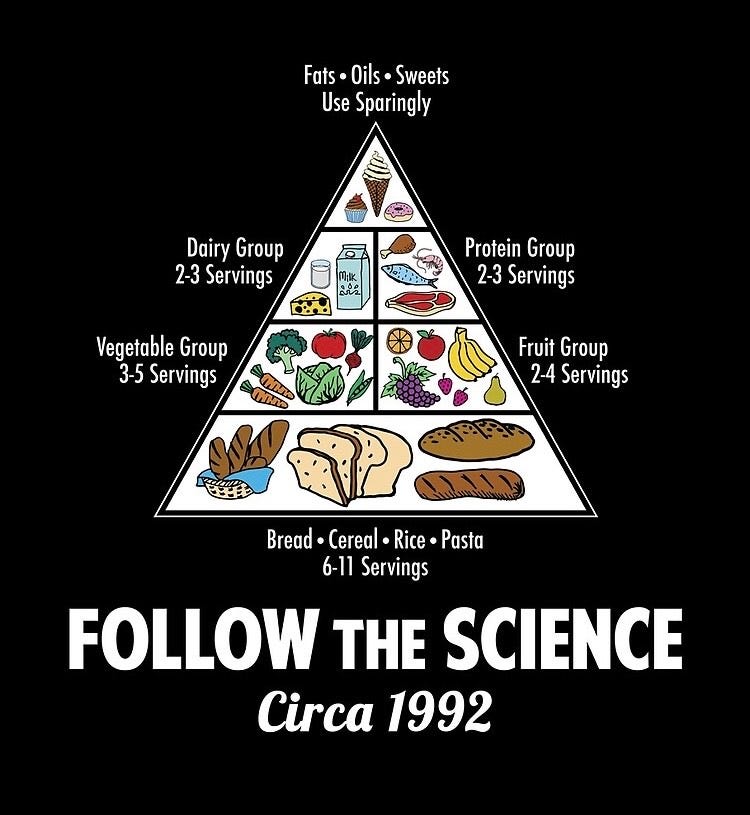

Let’s dig the food pyramid out of the memory hole and take a look at it. In 1992, the FDA’s official dietary advice for all Americans rested on a big bottom slab recommending 6-11 servings per day of bread, cereal, rice and pasta. Next came vegetables and fruits (3-5 servings and 2-4 servings), low-fat dairy and lean proteins (2-3 servings each), topped by “fats, oils and sweets” with the advice to “use sparingly.” These recommendations had their origins in the 1960s, when nutrition researcher Keys proposed the “diet-heart hypothesis”—that saturated fat and cholesterol cause heart disease—and convinced the American Heart Association (AHA) to adopt his findings.

In 1961, the AHA issued the first policy anywhere in the world advising the public to avoid saturated fat and dietary cholesterol as the best measure of prevention against heart attacks. Then, in the 1970s, the AHA refined its guidelines and suggested that the public cut back not just on saturated fat but all fat. In 1980, when the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services (USDA-HHS) co-issued the first dietary guidelines for the general population, these agencies adopted the AHA’s ideas on diet in full—and the government-endorsed low-fat, low-cholesterol diet was born.

At the same time that this advice unfurled across the nation, obesity in America began its distressing climb skyward. In 1960, our adult obesity rate was 9.6 percent. The numbers rose gently in the next two decades, but in 1980, the year the dietary guidelines were first published, data from the CDC shows a sharp increase. Today, the obesity rate is likely close to 50 percent, and diet-related chronic diseases are rampant. In 2014—the last year for which there are government numbers available—60 percent of American adults had one or more chronic diseases. An outside estimate put that rate at 88 percent in 2018. Today, we cannot remember being disease-free. Sickness is ubiquitous.

The study that Keys used to convince the AHA to adopt his proposals, the “Seven Countries Study,” has been enormously influential—yet its methodology reflected Keys’s bias towards his own hypothesis; and its conclusions have been repeatedly overturned in the years since. Keys compared data on diet and rates of heart diseases in seven countries, with the apparent finding that people who ate little saturated fat and cholesterol were less likely to die from heart disease. However, as I documented in my 2014 book, The Big Fat Surprise (and later in an academic paper), Keys cherry-picked the countries he studied, avoiding countries like Switzerland and France, where national statistics indicated that people had low rates of heart disease, yet ate plentiful meat and dairy. He also conveniently elided the fact that he collected dietary data from Crete during Lent. The strict Orthodox Greek fast excludes all animal foods, and did not represent the islanders’ usual diet.

Today, we are still living with the misguided ideas of this crusading scientist. Subsequent billions of dollars of testing over decades by the National Institute of Health have been unable to show that a diet low in fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol could reduce the risk of dying from heart disease; nor did these studies prove that a low-fat diet prevents heart disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, or cancer. In fact there is substantial evidence to the contrary. As most people now know from personal experience and common sense, a diet high in carbs and low in proteins and fats is not satiating, and causes us to eat more, with ill effects on our health. As for cholesterol, consuming dietary cholesterol has been proven to have no effect on blood cholesterol. (The guidelines dropped the numerical cap for cholesterol in 2015, but in typical government double-speak, they still say that healthy diets are “lower in cholesterol”.)

The food pyramid disappeared from government websites in 2011, replaced by MyPlate.gov, a vague, unhelpful kindergarten graphic. However, the nutritional advice has remained largely unchanged since the 1980s. The grain recommendation is lower, yet the USDA-HHS still says half our grains should be refined, despite widespread recognition that refined grains drive obesity and diabetes. (The refined version is included because only these are supplemented with synthetic nutrients; the government recommendations are already nutrient-deficient, and without refined grains, these shortfalls would be worse.)

Further, the guidelines allow up to 10 percent of calories from sugar, even though sugar is far from “just empty calories,” as we were once told, but rather actively unhealthy—and also contributes to chronic disease. The language suggesting that Americans “avoid too much fat” has disappeared, but the recommended fat level is still squarely within the range of the traditional “low-fat” diet.

People often say that no one follows the guidelines, so who cares? Yet the guidelines are arguably the key lever influencing what we consider to be healthy. All federal food programs are required by law to follow them, including school meals, feeding programs for women and infant children, the military (which has an obesity problem equal to the general population), the food in hospitals, and more. Most dieticians, nutritionists, nurses, and doctors take the guidelines as the gold standard. And many foods have been reformulated to comply with them—which is why we now have mostly lean and tasteless pork, and why low-fat yogurt and watery 1-2 percent milk are the only options in airports, at hotel buffets and so on. We are getting the guidelines whether we know it or not.

The best-available numbers confirm that Americans have followed the government’s advice. From 1965–2011, Americans reduced their fat consumption by 25 percent as a percent of total calories, while increasing carbohydrates by 30 percent. Between 1970 and 2014, the amount of red meat available in the U.S. food supply declined by 28 percent, whole milk by 79 percent, eggs by 13 percent, and animal fats by 27 percent. Meanwhile, the amount of fresh fruit available increased by 35 percent, vegetables by 20 percent, grains by 28 percent and vegetable oils by 87 percent—just as the guidelines advised.

If this diet worked, shouldn’t we have seen results already? And why would our nation’s top nutrition policy recommend foods that its own studies have repeatedly shown to be unhealthy? A non-profit I founded, the Nutrition Coalition, has spent the past decade campaigning to overturn the pyramid. In 2015, I wrote a story for the medical journal, The BMJ, documenting the government’s failure to review the relevant major clinical trials when formulating its approach. In response, a member of the USDA-HHS committee responsible for reviewing the science for the guidelines, Frank Hu, now the chair of the department of nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, launched a letter-writing campaign demanding that the article be retracted. Some 170 scientists and others signed on, though, as reported by The Guardian in 2016, none of the signees it interviewed were able to discuss the article’s supposed errors in detail. Ultimately, the BMJ stood by my research.

Congress is aware that the guidelines are problematic. In 2015, it allocated $1 million for a first-ever outside peer review of the guidelines process conducted by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). The review made 11 recommendations on how to improve transparency and scientific rigor in the guidelines-issuing process, but none have been significantly implemented.

I have also advocated for the USDA-HHS to review the large body of science on how a low-carbohydrate diet can prevent and treat chronic disease. More than 200 clinical trials now demonstrate that such diets can reverse type 2 diabetes, obesity, heart disease, NAFLD/MAFLD, and other chronic diseases, often within just weeks. Yet, the dietary guidelines process continues to ignore and suppress the scientific literature. For instance, a 2015 USDA review of low-carb diets found 40 studies and concluded that the method was superior to low-fat diets for weight loss. Nonetheless, USDA-HHS staff stuffed these results in the methodology section of the expert report—where they could not be considered for any final dietary recommendations. The committee also ignored recommendations by a member that this choice “[glossed] over recent evidence and [didn’t] give low-carb diets…sufficient attention that they deserve.” When the USDA subsequently reviewed low-carb diets in 2020, the resulting report disqualified all studies on the matter, including one funded by the NIH and authored in 2014 by a member of the USDA expert committee herself.

Whatever the reasons—the influence of various food lobbies, institutional overreach, reflexive self-defensiveness on the part of experts, or bureaucratic inertia—the USDA-HHS is persistently failing to bring its advice into compliance with an overwhelming body of scientific evidence that could improve the quality of American health and save lives. The new administration will have to attack the problem at its source if it wants to fulfill its promises.

Key takeaways:

- The US Dietary Guidelines for Americans are enormously influential, yet they have always been based on weak science, especially the advice to limit saturated fat and cholesterol, which is the reason that we erroneously believed that meat, whole milk, and butter are bad for health.

- Many people say that Americans don’t follow the guidelines, but the data since 1970 shows we have, including eating more fruits, vegetables, and grains, while reducing red meat, butter, and whole milk.

- A new edition of the guidelines, co-issued by the USDA and US-HH, is due out this fall.

As HHS Secretary Kennedy Moves to Unravel America’s Corrupt Food System, Native American Health Is Never Far From Mind

Breaking: HHS Secretary Kennedy Terminates 22 mRNA Vaccine Development Contracts

Join Cheryl Hines, Senator Rand Paul, & More for a MAHA Action Webinar on America's Broken Food System

Despite Legacy Media Shade, Presidential Fitness Test Will Return to Schools

BREAKING NEWS: Six More States Agree to End Taxpayer Subsidies of Junk Food

What You’re Not Being Told About Glyphosate–and Why It Matters

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.