Why the FDA’s Gluten Disclosure Move Matters to Families Like Mine

By Amy Sapola, PharmD, Functional Medicine Practitioner and Contributor, The MAHA Report

For years, people with gluten-related conditions have navigated the food system with vigilance rather than confidence—scrutinizing labels, managing uncertainty as a daily reality, and too often learning where the risks lie only after symptoms appear.

On January 21, the FDA announced an initiative that could forever change the lives of the gluten-intolerant. The federal government invited Americans to share their adverse reactions to gluten via a federal register, here, to better understand the scope of the problem and improve policies around it.

HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. explained, “Today, we advance the MAHA Strategy’s directive by demanding radical transparency in packaged food ingredients that affect health conditions and diet-related allergies.” He continued, “Americans deserve clear, reliable information about what’s in their food and how it’s made. Public input calling for honest labeling will protect consumers, prevent harm, and make America Healthy Again.”

As transparency, prevention, and patient voices increase, the conversation around gluten is shifting in a meaningful way, one that now depends on the public to help shape what comes next.

For many Americans, a food label is a formality. For families like mine, it is a risk assessment

I did not recognize gluten as the common thread behind my symptoms until my mid-thirties, despite years of severe gastrointestinal episodes that began in eighth grade and often left me on the bathroom floor, convinced I had food poisoning. As I eliminated more and more foods—tomatoes, grapes, cantaloupe—the list of supposed “triggers” grew, but the symptoms continued. The turning point came when my vision was affected. I removed gluten out of necessity, not certainty, and over the following months, the pattern became unmistakable: the gastrointestinal episodes stopped, and the other so-called food “allergies” resolved.

For my daughter, gluten exposure presents as a chronic, asthma-like cough—one that disrupts sleep, leads to being sent home “sick” from school, and defies easy explanation. Early on, it was treated as conventional asthma. Her pediatric pulmonologist was unequivocal: gluten could not possibly be the cause. There was no “evidence,” I was told, and my questions were met with visible irritation. He told me I should not “unnecessarily restrict her diet.” Medication, he insisted, was the only appropriate way to “control” her symptoms.

So we followed the protocol. Oral steroids. Inhaled steroids. Albuterol inhalers and nebulizers. Two different allergy medications. And still, she struggled to breathe. My husband and I spent countless nights sitting upright beside her bed, administering nebulizer treatment after nebulizer treatment, waiting and hoping she would finally breathe well enough to sleep.

Eventually, I reached a breaking point. We had already done everything we were told to do—and then some. We replaced the carpeting in our home, added air purifiers, encased her bedding, installed a vent hood over our gas stove—anything that might help. When none of it changed her breathing, I finally removed gluten from her diet. The improvement was not immediate, but over the course of two or three months it was unmistakable. Her cough resolved, her breathing normalized, and one by one, we discontinued every medication she was taking.

Today, she is medication-free, and her symptoms return only with accidental gluten exposure. The “impossible” had become undeniable.

We are not rare. We are undercounted.

Gluten-related disorders are not marginal. An estimated one percent of Americans have celiac disease, yet 60 to 70 percent remain undiagnosed, often for years or even decades. Beyond celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is believed to affect 0.6 to 6 percent of the population, a strikingly wide range that reflects how poorly defined, inconsistently recognized, and too often dismissed the condition remains in conventional medicine. These are not fringe diagnoses. They are common, routinely overlooked, and frequently minimized when standard testing fails to provide answers.

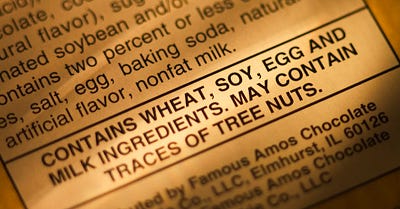

Compounding the problem is a persistent misunderstanding about where gluten actually comes from. Gluten is often treated as synonymous with wheat, but it exists not only in wheat—including durum, semolina, spelt, farro, einkorn, emmer, and kamut—but also in barley and rye, which remain less visible in public awareness and, critically, in labeling frameworks.

That is the core problem with U.S. gluten labeling: our system is built around wheat as an allergen, not gluten as a clinically meaningful exposure. Under the required allergen disclosure framework (FALCPA), manufacturers must disclose wheat, but not barley or rye, even though both contain gluten. “Gluten Free” is a voluntary marketing claim. This creates predictable blind spots, especially for families who believe “wheat-free” means safe, only to discover the consequences after symptoms return.

One of the most common—and most easily overlooked—sources of gluten is barley-derived malt, which is frequently used in flavors and extracts. Ingredients such as malt flavoring, malt extract, malt syrup, barley malt, malted barley, diastatic malt, non-diastatic malt, malt powder, and malt vinegar all typically contain gluten.

Another major blind spot is the catch-all term “natural flavors.” Under U.S. allergen labeling law, if a “natural flavor” contains wheat, it must be disclosed. However, if the flavoring is derived from barley or rye, disclosure is not required—despite the fact that both grains contain gluten.

Just as outdated as our current labeling is the assumption that gluten-related illness is primarily a digestive complaint. While classic celiac disease can cause intestinal damage and malabsorption, many patients, especially children and adults diagnosed later in life, never fit the textbook image. Instead, they present with extra-intestinal symptoms: migraines, anemia, infertility, mood changes, peripheral neuropathy, skin conditions, and respiratory symptoms.

NCGS does not produce the same intestinal injury, but its effects can be equally disruptive. Symptoms may emerge hours or even days after exposure and include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, nausea, brain fog, fatigue, headaches, joint or muscle pain, anxiety, depression, and skin rashes. And, as I know all too well, gluten reactions can also present beyond the gut—including respiratory symptoms such as chronic cough or asthma-like patterns, particularly in children.

Against this backdrop, the FDA’s January 21 announcement is consequential. The agency’s new Request for Information (RFI) on gluten ingredient disclosure and cross-contact in packaged foods is not a procedural formality. It is an acknowledgment that current labeling standards are insufficient, leaving families to navigate risk in the dark and too often pay for it with their health.

The RFI seeks public input on adverse reactions and labeling failures related to gluten-containing grains beyond wheat—specifically rye and barley—as well as oats, which are frequently contaminated during growing, transport, or processing.

The stakes are high. People with celiac disease are two to four times more likely to be hospitalized than the general population. Yet hospitalizations triggered by gluten exposure are underreported, because they are not coded as “gluten exposure.” Instead, they appear in medical records as acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage, severe dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, malnutrition, acute abdominal pain, complications of celiac disease, failure to thrive in children, or anemia.

Transparency is not a buzzword when my child’s breathing is affected—or when someone with celiac disease is hospitalized after eating a meal that was supposed to be safe. In those moments, labeling failures are not abstract regulatory gaps; they are medical events with real and lasting consequences.

For years, people with gluten-related conditions have been forced to “tiptoe around food,” as FDA Commissioner Marty Makary aptly put it. In practice, that tiptoeing is not cautious—it is exhausting. It means scrutinizing every ingredient list, calling manufacturers for clarification, declining invitations, packing food for events, and still risking reactions because rye or barley derivatives were never disclosed, or because oats—naturally gluten-free—were assumed safe despite widespread contamination.

From a clinical standpoint, this ambiguity carries real consequences. Gluten-related disorders are routinely misclassified as irritable bowel syndrome, unexplained anemia, anxiety, or poorly controlled asthma. Patients are reassured that their labs are “normal” if they do not meet narrow diagnostic criteria for celiac disease, even as symptoms persist. Children are placed on long-term medications without anyone asking the most basic upstream question: could food be the trigger?

The FDA’s own review concedes that “serious data gaps” limit its ability to assess the true public health impact of these exposures. Among the unanswered questions: How often are rye and barley present in packaged foods without clear disclosure? How severe are severe allergic (immunoglobulin E–mediated) reactions occurring to these grains? How pervasive is oat contamination with gluten-containing grains in real-world manufacturing?

Catherine Ebeling, RN, and a contributor to The MAHA Report, traces her journey with gluten-related illness back to the 1980s—long before gluten sensitivity was widely recognized or taken seriously. Reflecting on her experience, Catherine says, “In my forties, I started getting horrible rashes all over my face and neck whenever I ate even small amounts of gluten, so I got very strict about avoiding it. In the past 20 years, I’ve regained my health and digestive balance, gotten over the malabsorption, gut dysbiosis, joint aches, arthritis, asthma, rashes, etc. Now I’ve found that even foods labeled ‘Gluten Free’ often make me sick from the tapioca starch/cassava that is used as a wheat flour substitute.”

Her story underscores a reality many patients live with every day: even diligent label reading does not guarantee safety. This is precisely why the FDA’s RFI represents a meaningful opportunity. By collecting real-world data on adverse reactions and labeling failures, the agency can begin to close critical gaps, laying the groundwork for stronger disclosure standards, more accurate labeling, and regulatory policies that reflect lived experience rather than assumptions.

The FDA wants to hear from the public. The 60-day comment period under Docket No. FDA-2023-P-3942 is a chance for patients, parents, clinicians, and researchers to document experiences that have too often been minimized or ignored.

From a MAHA perspective, this effort reflects a broader shift: away from downstream symptom management and toward upstream accountability. You cannot Make America Healthy Again if the most basic input—food—is obscured by incomplete information. Transparency at the label level is foundational. It empowers informed choice, supports clinical care, and reduces preventable harm.

Radical transparency begins with understanding what is in our food and how it is grown, processed, and manufactured, so we are no longer forced to learn through trial and harm.

For families living with gluten-related conditions, transparency is not about preference or convenience; it is about safety, health, and trust. The FDA’s action reframes this challenge as an opportunity to rebuild confidence in our food system. That opportunity will only be realized if patients, caregivers, clinicians, and researchers speak up. The public comment period is open. This is the moment to share lived experience, submit data, and help shape future policy.

Your child probably doesn’t have asthma, she has silent reflux, which causes asthma like attacks when the stomach contacts reflux into the back of the throat. Typically there is a tremendous amount of mucus produced in the lungs, and this looks a lot like an asthma attack. I would be skeptical of the usual approach to do that which would be a proton pump inhibitor rather than attention to a diet and possibly the use of famotidine temporarily just at night. The problem is not excess acid in the stomach. The problem is a neuromuscular dyssynergia involving the lower esophageal sphincter caused in this case by gluten.

I am sorry doctors treated you the way they did. I practiced Neurology for 30 years and was the 1978 University of Virginia Jefferson fellow in medicine.

Rather than put money into labeling the source of this new "allergy" needs to be investigated. For example look into how glyphosate, which is in everything, affects the intestines.