"Unfounded"? RFK Jr.'s "Grain-Free Schizophrenia Cure" Is Backed by 75 Years of Research the Media Didn't Read.

Harvard. Stanford. McLean. The Published Remissions, the Double-Blind Trials, and the Media's Refusal to Look.

By Sayer Ji, Special to The MAHA Report

Read, share, can and comment on the X thread dedicated to this story here.

Zero. That is the number of researchers who have published peer-reviewed studies on diet and schizophrenia who were contacted by the journalists who called the science “unfounded.”

Story-at-a-glance

Seventy-five years of peer-reviewed research — including double-blind RCTs published in 2025 — link gluten-containing grains to schizophrenia in an identifiable subpopulation: the 25–30% of patients with elevated anti-gliadin antibodies.

Ketogenic and grain-free diets have produced documented remissions of schizophrenia at Harvard, Stanford, and McLean Hospital, with multiple RCTs now underway or completed. No journalist who covered Kennedy’s remarks contacted any of these researchers.

Wheat’s harm extends far beyond gluten. The Dark Side of Wheat identifies six categories of damage — including WGA neurotoxicity, opioid-receptor disruption, and excitotoxicity — across 335 peer-reviewed abstracts and 229 disease associations. Removing grains also eliminates chronic glyphosate exposure from pre-harvest desiccation.

The media called the science “unfounded.” The word they were looking for was “unread.”

The Claim, the Criticism, and the Missing Context

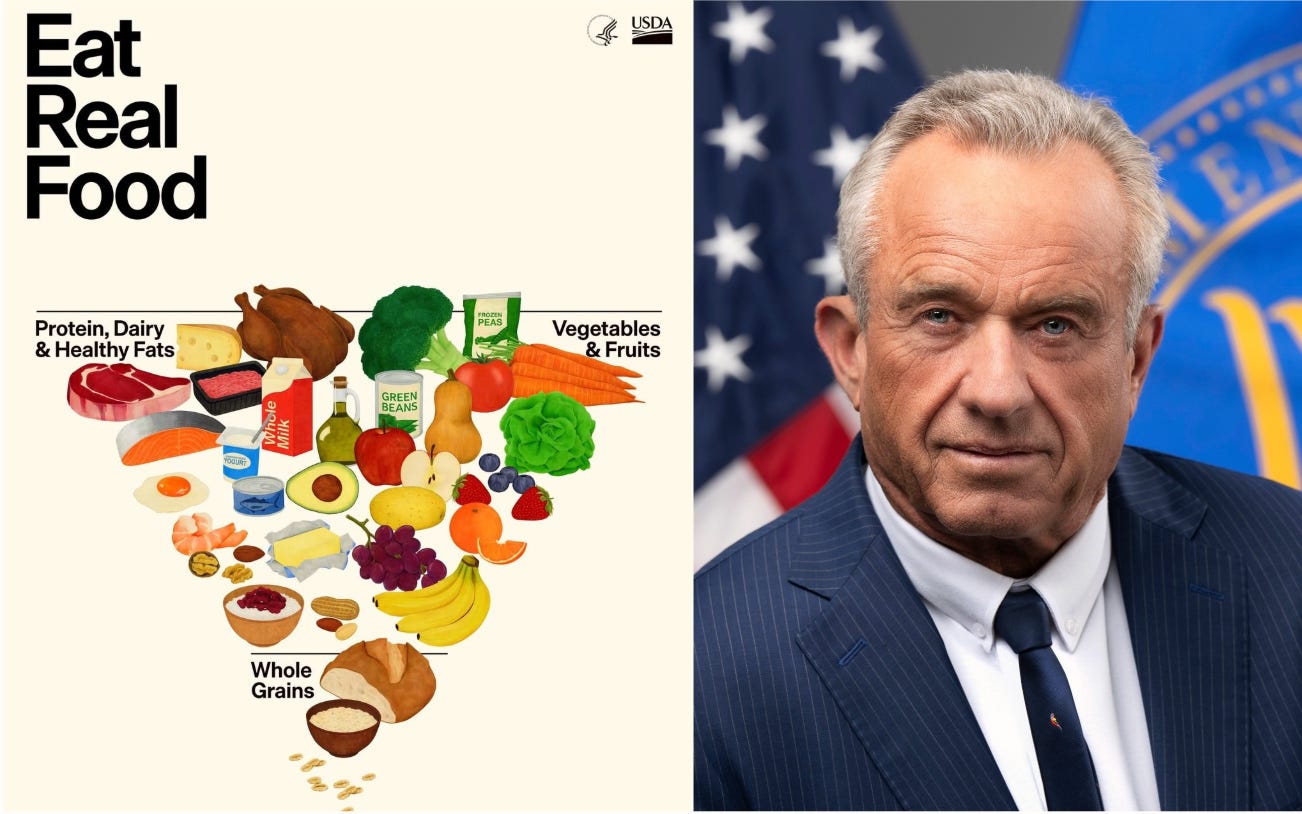

On February 4, 2026, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. told a crowd at the Tennessee State Capitol:

“We now know that the things that you eat are driving mental illness in this country. Dr. Chris Palmer at Harvard has cured schizophrenia using keto diets.”

He added:

“There are studies right now that I saw two days ago where people lose their bipolar diagnosis by changing their diet.”¹

At face value, critics are correct about one thing: the word cure is a blunt instrument in psychiatry, and Kennedy’s phrasing was rhetorically imprecise. But what followed was not careful scientific correction—it was narrative erasure. The coverage collapsed decades of metabolic psychiatry research, ignored documented clinical remissions, and substituted appeal-to-authority dismissals for engagement with the evidence. What was framed as an “unfounded claim” is, in fact, part of a 75-year body of research the media chose not to read.

Full disclosure: I have indexed peer-reviewed research on this topic for years, including a database on the therapeutic potential of ketogenic diets for bipolar disorder, viewable here. That is how I know that not one of the researchers behind these studies was contacted.

Within hours of Kennedy’s statement, the New York Times published a piece headlined “Kennedy Makes Unfounded Claim That Keto Diet Can ‘Cure’ Schizophrenia,”2 followed rapidly by nearly identical framings in The Independent3 and Raw Story.4 The coverage quoted two Columbia University psychiatrists — Dr. Paul S. Appelbaum, who called it “simply misleading,” and Dr. Mark Olfson, who stated flatly: “There is currently no credible evidence that ketogenic diets cure schizophrenia.”

Note carefully what is happening here. The media did not examine or refute the underlying research. It sought comment from two psychiatrists who have not conducted research on ketogenic therapy for schizophrenia, framed their authority-based dismissals as fact-checks, and closed the loop.

The Times did not contact Dr. Christopher Palmer of Harvard-affiliated McLean Hospital, whose published case studies Kennedy was directly referencing. It did not contact Dr. Shebani Sethi of Stanford, who coined the term “metabolic psychiatry” and led the pilot clinical trial that produced a 32% reduction in psychiatric symptom scores in schizophrenia patients on a ketogenic diet.5 It did not contact Dr. Deanna Kelly at the University of Maryland, whose research group just completed the first large-scale double-blind randomized controlled trial of a gluten-free diet in AGA IgG-positive schizophrenia patients.6 It did not contact Dr. Zoltan Sarnyai, whose formal RCT protocol for ketogenic metabolic therapy in schizophrenia was published in Frontiers in Nutrition in 2024.7

In other words, the journalists did not interview a single researcher who has actually studied the question.

And that refusal becomes increasingly difficult to justify in light of what the scientific literature actually shows.

What follows is a demonstration, grounded in 75 years of peer-reviewed evidence, that the relationship between dietary metabolic intervention and schizophrenia-spectrum remission is not “unfounded.” It is one of the most extensively documented — and systematically ignored — research trajectories in modern psychiatry.

75 Years of Research the Media Didn’t Read

The Earliest Clinical Observations: 1951–1957

Reports of the resolution of emotional disturbances following initiation of a gluten-free diet exist in the medical literature at least as far back as 1951.8 In 1954, Sleisenger reported discovering three schizophrenics among a group of thirty-two adults with celiac disease.9 In 1957, Bossak, Wang, and Aldersberg identified five psychotic patients among ninety-four patients with celiac disease.10 The initial recognition that celiac disease — or at least gluten sensitivity — occurred at a far higher prevalence among schizophrenics than in the general population opened the door to more elaborate investigation.

The Dohan Wartime Study: 1966

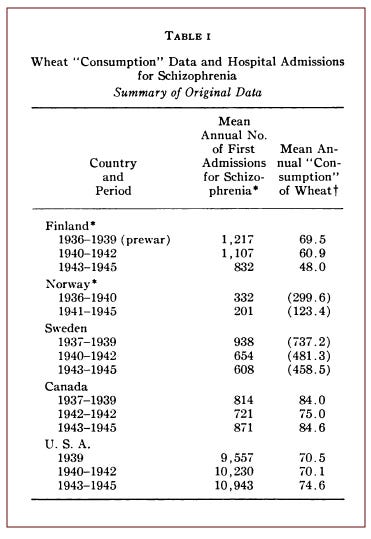

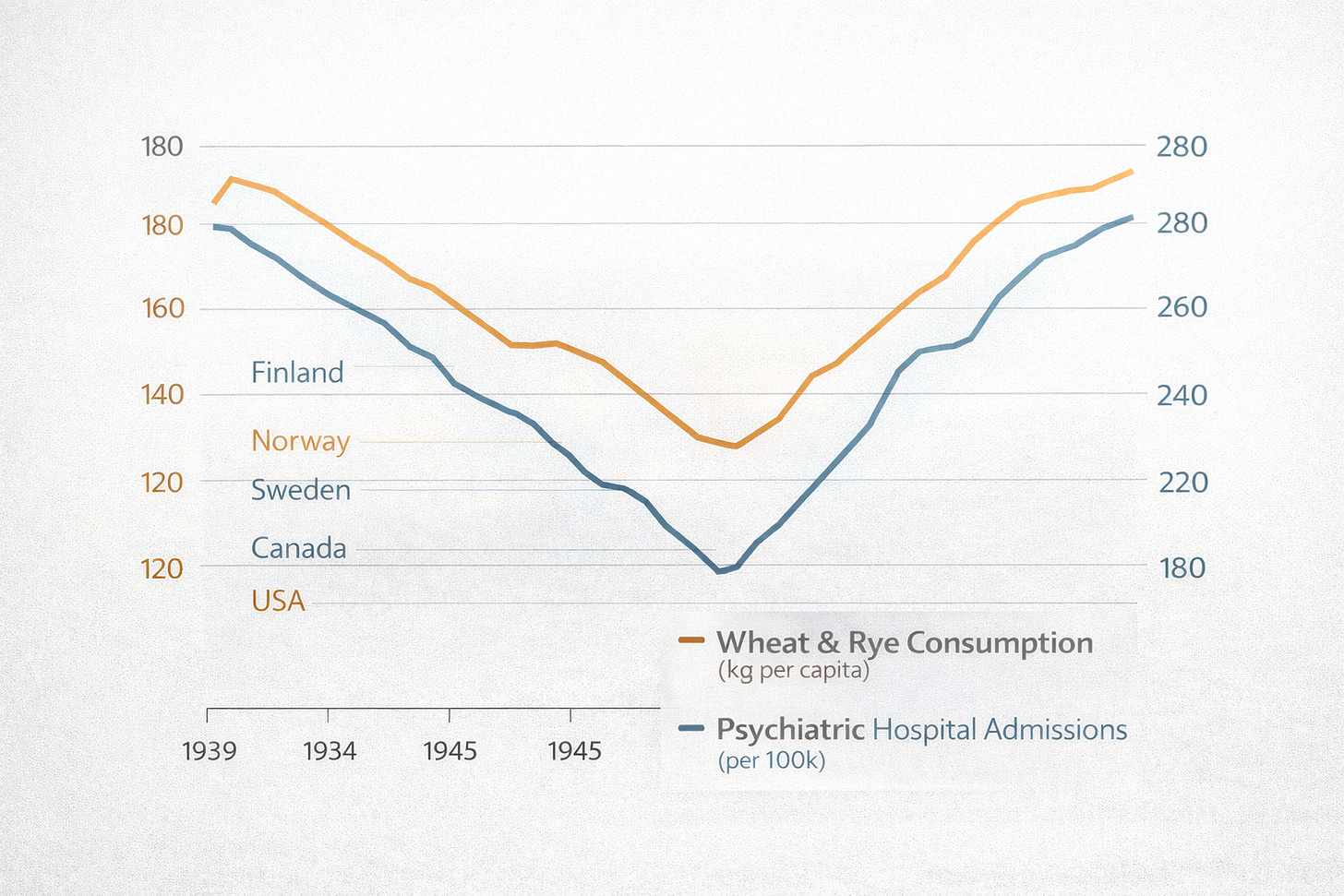

In 1966, a remarkable epidemiological study was published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition titled “Wheat ‘Consumption’ and Hospital Admissions for Schizophrenia During World War II.”11 The author, F. C. Dohan, M.D., compared the number of women admitted to mental hospitals in Finland, Norway, Sweden, Canada, and the United States before and after World War II, correlating these figures to the volume of wheat and rye consumed in each country.

The results were striking: the percent change from prewar values in first-time psychiatric admissions for schizophrenia was significantly correlated with the percent change in wheat and wheat-plus-rye consumption. As gluten grain rations decreased during the war, so did the rate of first-time admission to psychiatric institutions across five countries. When grain consumption returned to prewar levels, so did admissions.

Epidemiological Confirmation: Where Grain Is Rare, Schizophrenia Is Rare

In 1984, Dohan and colleagues published a landmark study in Biological Psychiatry examining psychiatric epidemiology in grain-free populations.12 Only two chronic schizophrenics were found among over 65,000 examined or closely observed adults in remote regions of Papua New Guinea (1950–1967), Malaita in the Solomon Islands (1980–1981), and Yap in Micronesia (1947–1948) — all populations that did not consume grains. When these peoples became partially Westernized and consumed wheat, barley beer, and rice, the prevalence of schizophrenia rose to European levels.

The Gluten Challenge: Proof of Causality in Science

In 1976, a study was published in Science — one of the world’s most prestigious peer-reviewed journals — demonstrating that schizophrenics maintained on a grain-free and milk-free diet who were challenged with gluten experienced interruption of their therapeutic progress.13 After termination of the gluten challenge, the course of improvement was reinstated. This is the dietary equivalent of a drug rechallenge study — the gold standard for establishing that a substance is causally linked to symptom expression.

Systematic Reviews Confirm the Pattern: 2006

A 2006 review published in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica surveyed the literature and found “a drastic reduction, if not full remission, of schizophrenic symptoms after initiation of gluten withdrawal” documented across a variety of studies.14

Anti-Gliadin Antibody Prevalence: The Immunological Smoking Gun

In 2011, a study in the Schizophrenia Bulletin found that persons with schizophrenia had seven-fold higher prevalence of antibodies related to celiac disease and gluten sensitivity than expected.15 A 2010 study in Schizophrenia Research demonstrated that this immune response to gliadin in schizophrenics was distinct from that of celiac disease — occurring without the typical transglutaminase antibodies or HLA-DQ2/DQ8 genetic markers — meaning that conventional celiac testing would miss it entirely.16

A 2018 study in the World Journal of Biological Psychiatry comparing 950 schizophrenics with 1,000 healthy controls found that the odds ratio of having anti-gliadin IgG antibodies was 2.13 times higher in schizophrenics.17

But it is the convergence of multiple studies that tells the most important story: approximately 25–30% of all schizophrenia patients carry elevated anti-gliadin antibodies of the IgG type (AGA IgG) — a rate significantly higher than the less-than-10% prevalence in healthy controls.18 This is not a marginal finding. It identifies a clinically actionable subpopulation comprising roughly one in three schizophrenia patients who may be experiencing immune-mediated neurological damage triggered by wheat proteins.

The Dark Side of Wheat: A Species-Wide Problem Hiding in Plain Sight

Long before the clinical trials of the 2020s, I published a comprehensive synthesis of the wheat-disease literature titled The Dark Side of Wheat: A Critical Appraisal of the Role of Wheat in Human Disease — a monograph drawing upon decades of peer-reviewed research across immunology, toxicology, neurology, and gastroenterology. Its central thesis was, and remains, profoundly disruptive to mainstream nutritional orthodoxy: celiac disease is not an aberrant reaction to a wholesome food, but the most visible expression of a species-wide intolerance to wheat that affects virtually everyone to varying degrees.

The conventional medical view treats celiac disease as a rare genetic defect — an unlucky mutation at the HLA-DQ locus on chromosome 6 that causes the body to attack itself when exposed to gluten. In this model, wheat is presumed innocent and the body guilty. The Dark Side of Wheat inverts this framework entirely. Drawing on the post-genomic revolution — particularly the discovery that monogenic diseases account for perhaps 1% of all disease, and that epigenetic factors, not genes alone, determine how DNA is expressed — the monograph argues that the celiac response may actually represent the body’s innate intelligence: a protective alarm system communicating that something inherently toxic has been consumed.

The Celiac Iceberg — And What Lies Beneath It

The monograph builds on the “celiac iceberg” metaphor introduced by Richard Logan in 1991, which recognized that the classical form of celiac disease — with its gross gastrointestinal symptoms, villous atrophy, and definitive biopsy — represents only the visible tip. Below the waterline lies an enormous mass of “silent” and “latent” celiac presentations, detectable only by serological screening, along with “out-of-the-intestine” manifestations that include neurological, psychiatric, dermatological, endocrine, and autoimmune disorders that are rarely traced to their dietary origin.

But The Dark Side of Wheat goes further. It proposes that the celiac iceberg is not free-floating — it is an outcropping from an entire submerged continent representing our species’ metabolic prehistory as hunter-gatherers, during which grain consumption was, in all likelihood, nonexistent except in cases of near-starvation. In biological time, the Neolithic agricultural revolution that introduced cereal grains into the human diet occurred only moments ago. The body cannot help but remember what the culture has forgotten.

23,788 Proteins — Not Just ‘Gluten’

One of the monograph’s most important contributions is its insistence that the conversation about wheat toxicity cannot be reduced to gluten alone. Common bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) has over 23,788 cataloged proteins, produced by a genome 6.5 times larger than the human genome, with six complete sets of chromosomes — three times our own. Each of these proteins carries a distinct potential for antigenicity. The clinical obsession with a single protein fraction — gliadin, the alcohol-soluble component of gluten — has obscured an entire landscape of immunotoxic, neurotoxic, and pharmacologically active compounds.

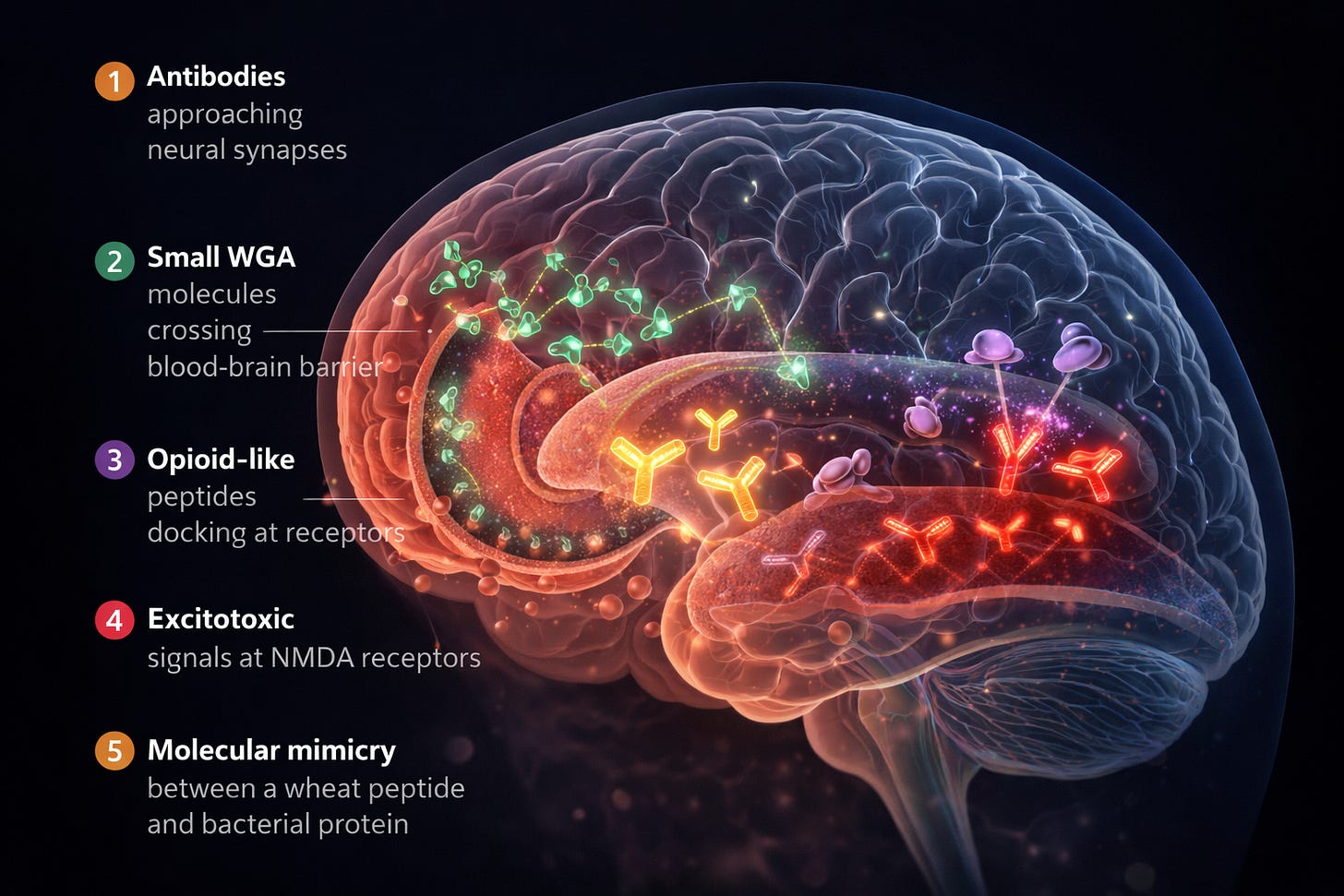

The Dark Side of Wheat identifies six distinct categories of harm, each supported by independent lines of peer-reviewed evidence: (1) gliadin-mediated immune destruction of intestinal tissue — not only in celiacs but in non-celiac individuals, as demonstrated in a landmark 2007 study in GUT showing that gliadin triggers innate immune responses in all intestines tested; (2) gliadin-induced zonulin upregulation causing intestinal permeability — the so-called “leaky gut” that allows macromolecules, including neuroactive peptides and bacterial endotoxins, to enter the bloodstream; (3) pharmacologically active opioid peptides (gluten exorphins A4, A5, B4, B5, C and gliadorphin) that pass through the blood-brain barrier and activate opioid receptors; (4) direct tissue damage by wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), a lectin capable of penetrating the blood-brain barrier via adsorptive endocytosis; (5) molecular mimicry, in which the 33-amino-acid gliadin peptide shares structural homology with pertactin, the immunodominant virulence factor in Bordetella pertussis; and (6) excitotoxicity from wheat’s exceptionally high levels of glutamic and aspartic acid, which over-activate NMDA and AMPA receptors.

The Invisible Thorn: WGA and the Blood-Brain Barrier

The wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) analysis is particularly relevant to the schizophrenia question. WGA is an extraordinarily small glycoprotein — just 36 kilodaltons — formed by the same disulfide bonds that make vulcanized rubber and human hair resistant to degradation. It is concentrated in the seed embryo of the wheat berry and is found at even higher concentrations in “whole wheat” and sprouted grain products than in their processed, fractionated equivalents. Unlike gluten sensitivity, which requires specific immune-mediated articulations, WGA can cause direct, non-immune-mediated damage to tissues in virtually every organ system without requiring any genetic predisposition whatsoever.

WGA’s neurotoxic potential is well-documented. It crosses the blood-brain barrier freely and is used in neuroscience as a tracer for mapping neural circuits — a testament to how efficiently it penetrates brain tissue. It binds to N-acetylneuraminic acid (sialic acid) on neuronal membranes, attaches to myelin sheaths, and inhibits nerve growth factor. At nanomolar concentrations — extraordinarily small quantities — WGA stimulates the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in intestinal and immune cells. A single one-ounce slice of bread contains approximately 500 micrograms of WGA. The monograph observes that WGA induces thymic atrophy, interferes with gene expression, disrupts endocrine function, exhibits insulin-mimetic activity contributing to weight gain and leptin resistance, and shares structural and functional similarities with certain viruses — including using the same sialic acid entry mechanism as influenza.

Wheat as a Drug: The Opioid Dimension

Perhaps the most culturally provocative argument in The Dark Side of Wheat concerns wheat’s pharmacological properties. The gluten exorphins and gliadorphins are not theoretical constructs — they are measurable opioid-receptor-activating peptides produced during the digestion of wheat proteins. The monograph proposes that these compounds may explain bread’s universal status as a “comfort food” and its apparently addictive qualities. Biologists Greg Wadley and Angus Martin reached similar conclusions, writing that cereals “are a food source as well as a drug” and that “a desire for the drug, even cravings or withdrawal, can be confused with hunger” — features that make cereals, in their words, “the ideal facilitator of civilization.”

The implications for schizophrenia are direct. If wheat produces opioid-like peptides that cross the blood-brain barrier and bind to opioid receptors, and if certain individuals — whether through genetic susceptibility, compromised gut permeability, or immune-mediated sensitivity — experience this effect more acutely than others, then what mainstream psychiatry classifies as endogenous psychosis may in some patients be an exogenous pharmacological reaction to a common dietary protein. This is precisely the hypothesis that the clinical evidence presented in the preceding and following sections of this article has begun to confirm.

335 Abstracts, 229 Disease Associations — And Counting

The GreenMedInfo research archive on wheat — compiled alongside and updated since the original monograph — now indexes 335 unique peer-reviewed abstracts documenting adverse health effects of wheat across 229 distinct disease associations, sourced from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.31 Among the indexed diseases: celiac disease (140 articles), gluten sensitivity (69), autoimmune diseases (12), food allergies (11), type 1 diabetes (13), autism spectrum disorders (7), schizophrenia (8), epilepsy (5), multiple sclerosis (3), cerebellar ataxia (4), and dozens more. The database represents what may be the most comprehensive curated collection of wheat-related biomedical research in existence — and it is entirely absent from the media coverage that dismissed Kennedy’s remarks as “unfounded.”

The question is not whether wheat can damage the brain. The question — answered in the affirmative by the clinical trials that follow — is how many schizophrenia patients are currently suffering from an identifiable, testable, treatable dietary exposure that no one has thought to investigate.

The Evidence Has Exploded Since 2018 — And It’s No Longer ‘Preliminary’

The media coverage in February 2026 repeatedly characterized the research as “very preliminary” and consisting of “small short-term studies.” This framing was accurate circa 2018. It is no longer accurate in 2026. The field has advanced dramatically in the intervening years, across multiple converging research tracks.

The First Double-Blind RCT of Gluten-Free Diet in Schizophrenia (2019, 2025)

Dr. Deanna Kelly and her colleagues at the University of Maryland’s Psychiatric Research Center conducted the first double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of a gluten-free diet in schizophrenia patients who tested positive for AGA IgG. In the initial 2019 pilot (N=16), participants were admitted to an inpatient unit for 5 weeks and randomized to receive either 10g of gluten flour or 10g of rice flour in a daily shake, while all meals were standardized gluten-free. The gluten-free group showed improvement in psychiatric symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, and reductions in the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-23.19

In February 2025, the confirmatory trial was published (N=39), representing the first large-scale double-blind RCT in this population. Results showed significant improvement in negative symptoms — particularly anhedonia and avolition — in the gluten-free group compared to the gluten-containing group.6 This is critical because no FDA-approved treatment currently exists for negative symptoms of schizophrenia, which are the primary determinants of functional impairment.

To be explicit: we now have double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial data — the gold standard of clinical evidence — showing that removal of gluten improves schizophrenia symptoms in patients identified by a simple blood test. This is precisely the kind of evidence the New York Times claims does not exist.

Gluten-Free Diet Lowers Oxidative Stress in Schizophrenia (2024)

In a companion analysis of the pilot trial’s banked plasma samples, Kim et al. (2024) demonstrated that the gluten-free diet measurably reduced oxidative stress in gluten-sensitive schizophrenia patients, and that this reduction was correlated with improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms, negative psychiatric symptoms, and decreases in the inflammatory cytokine IL-23.20 This provides biomarker-level mechanistic evidence — not mere symptom reports — that gluten removal produces objective physiological changes in these patients.

Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia Responds to Gluten Restriction (2022)

A 2022 case report in Schizophrenia Research documented a patient with treatment-resistant schizophrenia — a patient for whom conventional pharmaceutical interventions had failed — whose AGA IgG levels were significantly elevated and who responded to a gluten-restricted diet where medications had not succeeded.21 Notably, mean plasma concentrations of AGA IgG in treatment-resistant schizophrenia patients have been found to be significantly higher than in non-treatment-resistant patients, suggesting that the most intractable cases may be precisely those most likely to benefit from dietary intervention.

The Novel Gliadin Peptide Discovery (2017)

A 2017 study in Translational Psychiatry deepened the mechanistic picture by showing that schizophrenia patients mount antibodies against indigestible gliadin-derived peptides — specifically a γ-gliadin fragment designated AAQ6C — rather than against the native gliadin molecules that trigger celiac disease.22 This finding explains why conventional celiac disease testing fails to identify the gluten-schizophrenia connection: the immune system in schizophrenia is reacting to different wheat-derived fragments than those screened by standard diagnostics.

Maternal Gluten Sensitivity and Offspring Psychosis Risk

A Karolinska Institutet study examining 764 birth records and neonatal blood samples of Swedes born between 1975 and 1985 found that children born to mothers with abnormally high levels of antibodies to gliadin had nearly twice the risk of developing non-affective psychosis, including schizophrenia, later in life.23 Because a mother’s antibodies cross the placenta during pregnancy, this finding suggests that the gluten-schizophrenia connection may begin in utero — raising questions about whether maternal diet during pregnancy constitutes an underrecognized risk factor for psychiatric illness in offspring.

The Ketogenic Convergence: Metabolic Psychiatry Arrives

The media coverage of Kennedy’s remarks treated his reference to ketogenic therapy and his comments about food driving mental illness as though they were disconnected, fringe ideas. In fact, they represent two faces of the same rapidly advancing scientific paradigm: metabolic psychiatry.

The term was coined by Dr. Shebani Sethi of Stanford Medicine, who founded the first Metabolic Psychiatry clinic at a major academic medical center.24 The field’s central thesis is that psychiatric disorders — including those historically considered “incurable” — may be expressions of disordered brain energy metabolism, and that interventions which restore metabolic function may improve or reverse psychiatric symptoms.

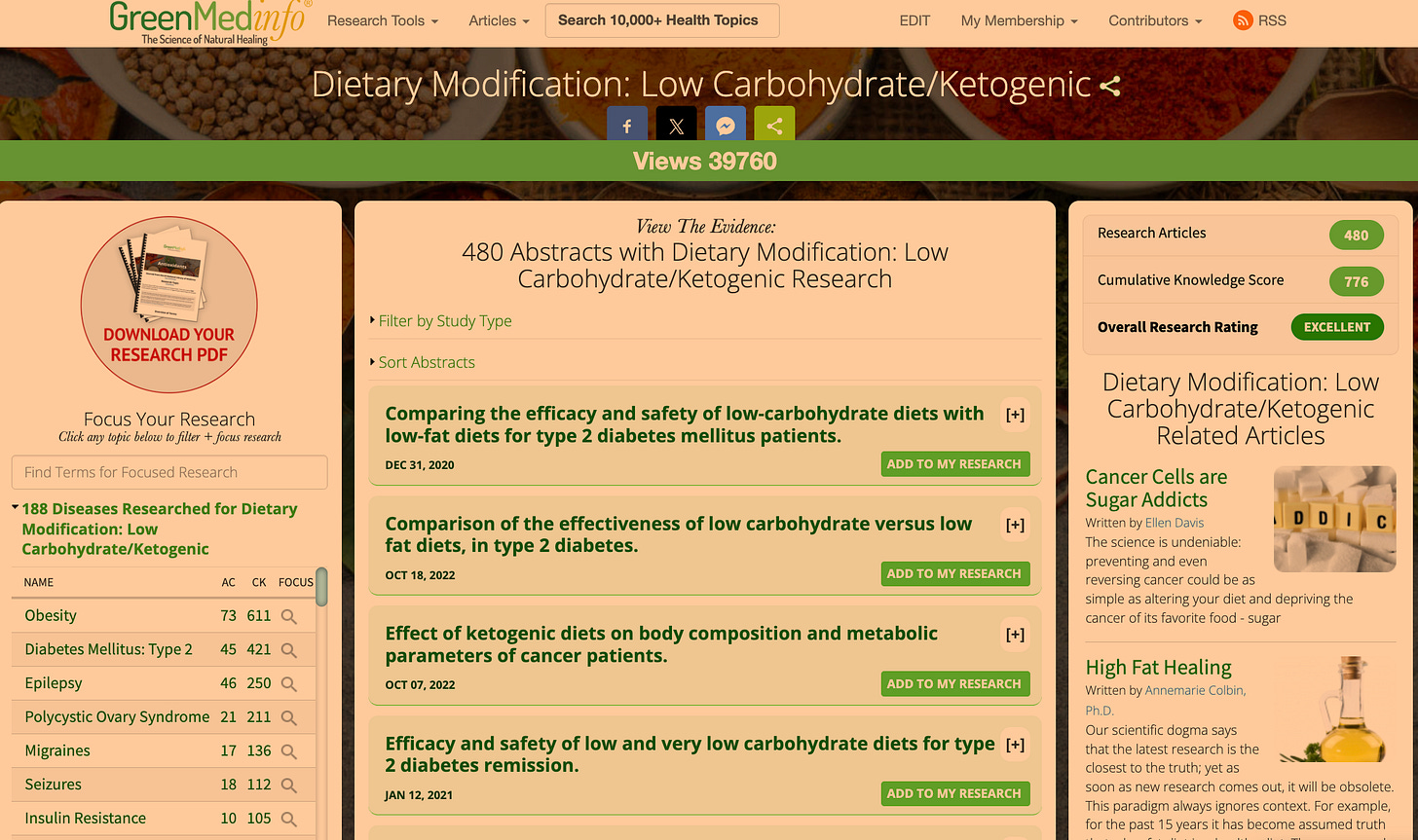

The psychiatric applications of ketogenic therapy are, in fact, only one corner of a vast and rapidly growing evidence base. The GreenMedInfo research archive on ketogenic/low carbohydrate diets indexes 475 unique peer-reviewed studies on low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets, documenting potential therapeutic value across 183 distinct disease conditions — from obesity (73 studies) and type 2 diabetes (45 studies) to epilepsy (46 studies), Alzheimer’s disease (34 studies), polycystic ovary syndrome (21 studies), inflammation (21 studies), cancer (15 studies), autism spectrum disorders (15 studies), Parkinson’s disease (13 studies), depression (13 studies), multiple sclerosis (11 studies), glioblastoma (9 studies), bipolar disorder (7 studies), and schizophrenia.45 The archive further catalogs 66 distinct pharmacological actions of ketogenic diets confirmed in research, including neuroprotective (78 studies), anti-inflammatory (73 studies), anticonvulsant (51 studies), hypoglycemic (41 studies), antioxidant (31 studies), chemotherapeutic (28 studies), gastrointestinal (26 studies), hypolipidemic (24 studies), and antidepressive (10 studies) effects. This is not a fad diet with anecdotal backing. It is a metabolic intervention with a research footprint rivaling many pharmaceutical classes.

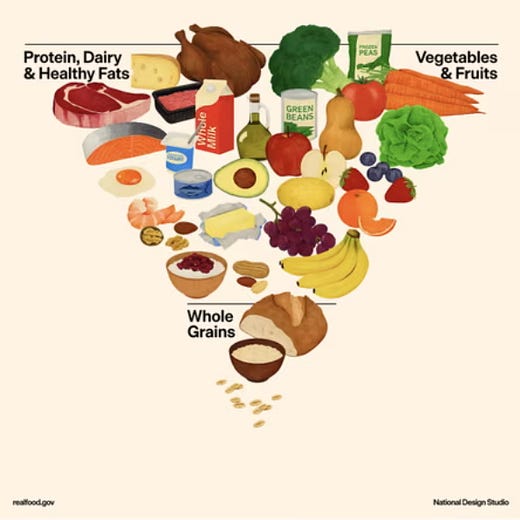

The ketogenic diet is the leading clinical tool in this paradigm. And here is the critical connection that the media entirely missed: a ketogenic diet inherently eliminates wheat and gluten. This means that the benefits observed in ketogenic therapy trials may be operating through both metabolic fuel-switching (providing ketone bodies as alternative cerebral fuel) and the removal of immunotoxic, neuroactive wheat proteins. There is also a third, frequently overlooked mechanism: eliminating gluten-containing grains simultaneously eliminates a major source of glyphosate exposure. Glyphosate — the active ingredient in Roundup — is widely used as a pre-harvest desiccant on conventional wheat, barley, and oats, sprayed directly onto the mature crop to accelerate drying before harvest. This means that non-organic wheat products carry residues of a chemical classified by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a probable human carcinogen, and which has been shown in peer-reviewed research to disrupt the gut microbiome, impair tight junction integrity, chelate essential minerals, and interfere with cytochrome P450 enzyme pathways critical for neurological function. When a patient removes wheat from the diet — whether through a ketogenic, gluten-free, or grain-free protocol — they are not merely removing gluten and WGA. They are removing a chronic, low-dose pesticide exposure whose neurotoxic and endocrine-disrupting potential has yet to be fully accounted for in any psychiatric intervention trial. These are not competing hypotheses. They are convergent mechanisms.

Palmer’s Case Studies: Documented Remission at Harvard

Kennedy’s specific reference was to Dr. Christopher Palmer, Director of the Metabolic and Mental Health Program at Harvard-affiliated McLean Hospital. The New York Times acknowledged Palmer’s research but characterized it dismissively. Here is what Palmer’s published record actually shows:

In 2017, Palmer published two case studies of patients with longstanding, treatment-resistant schizoaffective disorder who started a ketogenic diet for weight loss. Within two months, both patients experienced significant reductions in psychotic symptoms as measured by the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS). When both patients stopped the diet — one deliberately, one inadvertently — their psychotic symptoms returned quickly. When they resumed the diet, symptoms abated again, demonstrating an “on/off” effect analogous to a medication.25

In 2019, Palmer and colleagues published two additional case studies in Schizophrenia Research involving patients with long-standing schizophrenia who experienced complete remission of psychotic symptoms on a ketogenic diet. Both patients “were able to stop antipsychotic medications and have remained in remission for years now.”26 One patient, an 82-year-old woman with schizophrenia since her teens, had been unable to function independently for decades. After initiating a ketogenic diet, she experienced the first symptom remission since 1993 and has been off antipsychotic medication for years.

These are the specific cases Kennedy referenced. The Times acknowledged their existence — then buried them under the word “unfounded.”

Stanford Pilot Trial: 32% Psychiatric Symptom Reduction (2024)

Dr. Sethi’s four-month pilot trial at Stanford enrolled 21 adult participants diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, all taking antipsychotic medications and exhibiting metabolic abnormalities.5 Results:

Participants with schizophrenia showed a 32% reduction in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. Overall Clinical Global Impression severity improved by an average of 31%, with 79% of participants who started with elevated symptomatology showing clinically meaningful improvement. Adherent participants experienced significant reductions in weight (12%), BMI (12%), waist circumference (13%), visceral adipose tissue (36%), and HOMA-IR insulin resistance (27%).

As Sethi noted: “The participants reported improvements in their energy, sleep, mood and quality of life. They feel healthier and more hopeful.”24 The Columbia psychiatrists quoted by the Times dismissed this study as “very preliminary evidence” that the diet “might be helpful.” A 32% reduction in psychiatric symptom scores with 79% clinically meaningful response rate is not a trivial finding. Most pharmaceutical interventions for schizophrenia would consider such outcomes highly significant.

Frontiers in Nutrition Case Report: Full Remission (2025)

Published in Frontiers in Nutrition in 2025, a case report documented a patient with schizophrenia who, under nutritional therapy practitioner support, adopted a carnivore ketogenic diet. Within nine months, his mental health team formally noted his schizophrenia was in remission.27 He came off all psychiatric medications, his community treatment order was discharged, and he maintained stable nutritional ketosis with blood ketone levels between 3 and 4 mmol/L. He remains stable.

The Field Is Now Moving to Large-Scale RCTs

The claim that this research is merely “preliminary” ignores the trajectory. Formal randomized controlled trial protocols are now published and underway:

Longhitano, Sarnyai, and colleagues published a 14-week RCT protocol in Frontiers in Nutrition (2024) for 100 participants with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder, randomized to a modified ketogenic diet versus standard Australian dietary guidelines.7 UCSF has launched a 7T MRI mechanistic trial (NCT05268809) randomizing 70 participants to ketogenic versus standard diet, with neuroimaging to directly measure neural network instability before and after intervention.28 McLean Hospital has established a dedicated Metabolic and Mental Health Program under Palmer’s direction, with clinical trials underway.29

A comprehensive 2025 review in Frontiers in Pharmacology synthesized the preclinical and clinical evidence, concluding that ketogenic therapy “attenuates neuroinflammation by modulating astrocytic and microglial responses, lowering proinflammatory cytokines“ including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α.30

Behind much of this institutional momentum stands an organization the mainstream media has entirely ignored: Metabolic Mind, founded by Jan Ellison Baszucki — a Stanford-educated writer, mental health advocate, and mother whose own son recovered from bipolar disorder through metabolic psychiatry.47 Metabolic Mind has become the central hub connecting researchers, clinicians, and patients in the emerging field — curating clinical evidence, funding research, training providers, and collecting recovery stories from individuals who have experienced firsthand what the published literature now confirms. That a dedicated nonprofit with deep institutional partnerships is building the infrastructure for metabolic psychiatry — offering clinician training, patient support programs, and a searchable research database — is not the hallmark of a “fringe” idea. It is the architecture of a paradigm in formation.

Five Mechanistic Pathways: Why This Works

Understanding why dietary and ketogenic interventions can affect schizophrenia requires understanding what they remove and what they restore. The GreenMedInfo research archive documents over 200 adverse health effects of gluten-containing grains, with 342 unique research articles indexed across 232 disease associations.31 The Dark Side of Wheat synthesizes this evidence into a coherent framework identifying at least five distinct pathways through which wheat proteins may contribute to psychiatric and neurological pathology.32

Pathway 1: Immune-Mediated Neurotoxicity — Anti-Gliadin Antibodies Attack the Nervous System

A 2007 study in the Journal of Immunology demonstrated that anti-gliadin antibodies bind to neuronal synapsin I, a protein found within the nerve terminals of axons.33 The study authors proposed this molecular cross-reactivity as the mechanism by which gliadin contributes to “neurologic complications such as neuropathy, ataxia, seizures, and neurobehavioral changes.” A 2004 study in Nutritional Neuroscience found that children with autism simultaneously show antibody elevations against both gliadin and cerebellar (brain) proteins — indicating that wheat proteins may stimulate antibodies that cross-react with and damage brain tissue.34

Pathway 2: Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration by Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA)

Wheat germ agglutinin, the lectin component of wheat, possesses a property that most dietary proteins do not: it can cross the blood-brain barrier through a process called “adsorptive endocytosis” and travel freely among brain tissues.35 This capacity is so well established that WGA is routinely used in neuroscience as a tracer for mapping neural circuits. WGA binds to N-acetylneuraminic acid, a critical component of neuronal membranes including gangliosides, whose dysfunction is implicated in neurodegenerative disorders. WGA can attach to the myelin sheath protecting nerves, is capable of inhibiting nerve growth factor, and at nanomolar concentrations stimulates the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines including Interleukin 1, Interleukin 6, and Interleukin 8 in intestinal and immune cells.32

Pathway 3: Opioid-Receptor Disruption via Gluten Exorphins

The digestion of wheat gluten produces opioid-like peptides — gluten exorphins A4, A5, B4, B5, C, and gliadorphin — that can pass through the blood-brain barrier via circumventricular organs and activate opioid receptors, resulting in disrupted brain function.32 These peptides have been hypothesized to play a role in autism, schizophrenia, ADHD, and related neurological conditions. As The Dark Side of Wheat argues, the difference between a person diagnosed with schizophrenia and a functional wheat consumer may not be a categorical distinction but a difference in degree of susceptibility to the same pharmacologically active compounds.

Pathway 4: Excitotoxicity from Glutamic and Aspartic Acid

Of all commonly consumed cereal grasses, wheat contains the highest levels of the non-essential amino acids glutamic acid and aspartic acid. These amino acids, at elevated concentrations, cause over-activation of NMDA and AMPA nerve cell receptors, leading to calcium-induced nerve and brain injury — a process known as excitotoxicity.32 This mechanism is directly relevant to schizophrenia, where NMDA receptor hypofunction is one of the leading pathophysiological models. Glutamic acid is the compound responsible for wheat’s “umami” flavor — the same compound that, in its synthetic form (monosodium glutamate), has long been recognized as a potent neurostimulant.

Pathway 5: Molecular Mimicry

The digestion of gliadin produces a 33-amino-acid peptide known as the 33-mer, which exhibits remarkable structural homology with pertactin, the immunodominant sequence of the Bordetella pertussis bacterium (whooping cough).32 Pertactin is a highly immunogenic virulence factor used in vaccines to amplify immune response. The structural similarity between this gliadin-derived peptide and a known pathogenic protein creates the conditions for the immune system to confuse a dietary protein with a dangerous invader — potentially triggering cell-mediated or adaptive immune responses against self-tissues, including neural structures.

Taken together, these five pathways represent a comprehensive, multi-system explanation for why the removal of wheat — whether through a gluten-free diet, a ketogenic diet, or both — can produce measurable neuropsychiatric improvement. They are not speculative. Each is grounded in published, peer-reviewed research. And when a ketogenic diet removes wheat while simultaneously providing alternative cerebral fuel, reducing neuroinflammation, stabilizing glutamate/GABA signaling, and improving mitochondrial efficiency, it is addressing multiple pathogenic mechanisms simultaneously.

Anatomy of a Non-Engagement: Where the Media Criticism Overreaches

A serious fact-check would have engaged the evidence and identified what Kennedy overstated, what he got right, and what remains uncertain. Instead, the coverage committed several specific errors of framing that deserve scrutiny.

Error 1: Conflating Imprecise Language with Invalid Science

The word “cure” is imprecise in this context. But Kennedy did not invent the underlying research. He referenced a named researcher — Dr. Christopher Palmer — who has published case studies documenting complete remission of schizophrenia symptoms with discontinuation of antipsychotic medications sustained over years. Palmer himself, and his institutional sponsor McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School, have publicly described these outcomes. The research exists. The remissions are documented. The imprecision is in the word “cure,” not in the existence of the evidence.

Error 2: Quoting Non-Researchers as Authorities on Research They Have Not Conducted

The Times quoted Dr. Appelbaum, a past president of the American Psychiatric Association, and Dr. Olfson, both at Columbia. Neither has published research on ketogenic therapy or dietary intervention for schizophrenia. Their statements — while reflecting mainstream psychiatric caution — do not constitute engagement with the science. Not a single researcher who has actually conducted the relevant studies was quoted in any of the three articles.

Error 3: Characterizing the Stanford Study as Lacking a Control Group

The Times noted that “most of the studies” testing ketogenic diets for mental health “did not include a control group.” This is technically true of the Stanford pilot, which was a single-arm trial. But it entirely omits the existence of Dr. Kelly’s double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs at the University of Maryland (2019 and 2025), which did include control groups and did demonstrate significant benefit. It also omits the 1976 gluten-challenge study published in Science, which demonstrated causality through dietary rechallenge. By selectively acknowledging only the weakest study design and ignoring the strongest, the coverage creates a systematically misleading impression.

Error 4: Claiming ‘No Credible Evidence’ While Credible Evidence Accumulates

Dr. Olfson’s statement — “There is currently no credible evidence that ketogenic diets cure schizophrenia” — is defensible only if “credible evidence” is defined as large-scale, multi-site, long-term RCTs with replication. By that standard, the statement is technically true. But by that standard, the same sentence could have been written about the ketogenic diet’s effect on epilepsy in 1998, about H. pylori’s role in peptic ulcers before Barry Marshall’s self-experimentation, or about nearly every paradigm-shifting medical insight in its early clinical phase.

What we do have — double-blind RCTs, published case series with sustained remission, pilot trials with measurable biomarker changes, five identified mechanistic pathways, animal models, 75 years of epidemiological concordance, and published protocols for large-scale confirmatory trials — constitutes a substantial and growing evidence base, not an absence of evidence.

Error 5: Ad Hominem Framing Substitutes for Substantive Engagement

All three articles embedded Kennedy’s dietary claims within a recitation of his most controversial historical statements — on HIV, on COVID-19, on vaccines. The rhetorical effect is to invite readers to dismiss the dietary science by association. But the validity of the gluten-schizophrenia research does not depend on Kennedy’s credibility. It depends on the work of Dohan, Singh, Cascella, Kelly, Palmer, Sethi, Sarnyai, Alaedini, and dozens of other researchers across six decades. Attacking the messenger to avoid the message is not journalism. It is a familiar form of intellectual evasion.

What Kennedy Got Right — And What Responsible Science Now Allows Us To Say

A defensible summary of the current evidence:

Ketogenic and gluten-free dietary therapies are biologically plausible, mechanistically supported through at least five identified pathways, and clinically observed to produce symptom improvement — including documented cases of full remission and antipsychotic medication discontinuation — in subsets of individuals with schizophrenia and related disorders. The most responsive subpopulation appears to be patients with elevated anti-gliadin IgG antibodies, comprising approximately 25–30% of schizophrenia patients. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evidence confirms benefit in this subgroup. While not yet established as universal cures, these interventions warrant serious, adequately funded investigation rather than opportunistic dismissal.

Kennedy’s core assertions — that diet affects mental illness, that a Harvard researcher has documented remission of schizophrenia using a ketogenic diet, and that studies exist showing loss of psychiatric diagnoses through dietary change — are all factually correct. His use of the word “cure” was imprecise and should have been qualified. But the media’s choice to treat the entire claim as fabrication, rather than an overstatement of real science, is a far greater distortion than the one it purports to correct.

A Note on What Is Actually Dangerous

The Times and Independent framed Kennedy’s remarks as potentially “dangerous.” Consider what is actually at stake. Schizophrenia carries a life expectancy shortened by 15 to 20 years.30 The cost to the U.S. economy is estimated at $366.8 billion per year.36 Antipsychotic medications — the current first-line treatment — cause weight gain, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, contributing to the very mortality they are supposed to prevent. Treatment resistance is common. Full remission is rare.

It is not “dangerous” to explore dietary interventions for a condition with catastrophic outcomes and limited therapeutic options, particularly when those interventions are supported by seven decades of converging evidence and are now the subject of formal clinical trials at Stanford, Harvard, UCSF, and the University of Maryland.

What is dangerous is a media environment that reflexively suppresses promising avenues of investigation because they challenge established therapeutic frameworks and the pharmaceutical revenue streams that depend on them.

To warn the public against exaggerated claims is appropriate. To dismiss an entire research trajectory by caricature is not.

Conclusion

The relationship between wheat, gluten, metabolic dysfunction, and schizophrenia is not new. It is not fringe. It is not a conspiracy. It is a research trajectory spanning 75 years, published in Science, Biological Psychiatry, the Schizophrenia Bulletin, Translational Psychiatry, Schizophrenia Research, the Journal of Immunology, Psychiatry Research, Frontiers in Nutrition, Frontiers in Pharmacology, and the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, among others.

When a field of research reaches the point where it has wartime epidemiology, grain-free population studies, gluten-challenge causality data, seven-fold antibody prevalence, novel immune response characterization, anti-gliadin cross-reactivity with neural tissue, double-blind RCTs, biomarker-confirmed oxidative stress reduction, documented sustained remissions off medication, published RCT protocols at four major academic institutions, and a comprehensive mechanistic framework involving five distinct pathogenic pathways — the question is no longer whether the evidence exists.

The question is why the institutions that claim to serve the public interest — media, medical establishment, regulatory bodies — continue to treat this evidence as though it does not.

Your first-hand experience matters. If you remove gluten-containing grains from your diet and your physical or mental health improves, no fact-check can override what your body is telling you. For those living with schizophrenia, the AGA IgG blood test offers a simple, actionable starting point for determining whether you may be among the 25–30% most likely to benefit from dietary intervention.

The evidence is no longer preliminary. The institutions are simply not ready to hear it.

I am constantly impressed by RFK Jr’s relentless push to help us with our health in the face of all the evil naysayers who won’t even consider and contemplate what he is saying. I wish him the very best and thank him for his work. It is patently obvious that we have an epidemic of mental illness in this country. It seems obvious that diet would impact physical and mental health, but when you eat from fast food, boxes, and cans, maybe your brain cannot connect the dots and maybe that is intentional.

Clearly, they’ve been brainwashed or sold out to big Pharma. It’s relentless because there’s a knee-jerk reaction against anything in the administration. And it’s really easy to do right now because of the way everything is being handled except for RFK. I’m so grateful that he’s willing to give himself to this work at the age of 70.