Nutrition Science Is Broken. MAHA’s Mission to Fix it Matters Now More Than Ever

By Dr. Cate Shanahan, Special to The MAHA Report

Robert F. Kennedy Kr. and members of the MAHA movement are asking the right questions. They see the corruption in medicine and public health, and they’re determined to rebuild trust in science from the ground up.

But when it comes to nutrition, the corruption runs far deeper than most people realize. It isn’t just about improving dietary guidelines or reforming farm policy. It’s about confronting the faulty science that has shaped every part of our food system and our medical thinking for nearly a century.

That broken science began with a single idea — the belief that cholesterol causes heart disease.

The Great Cholesterol Panic

To understand how nutrition science went off the rails, we have to return to a moment of national panic.

Shortly after World War II, America was gripped by a terrifying new epidemic. Men in their 40s and 50s, seemingly healthy, strong, and in the prime of their lives, were clutching their chests, keeling forward, and collapsing dead. The cause? They called it “a coronary,” what we now call a heart attack. While commonplace today, heart attacks had been so rare in the early 1900s that cardiologists could go their entire careers without seeing one. By the 1950s, they were killing nearly half of America’s men.

The fear was visceral. “Dropping dead” became part of our national vocabulary. Newspapers ran headlines about executives dying at their desks. Television dramatized the horror. Americans were desperate for answers.

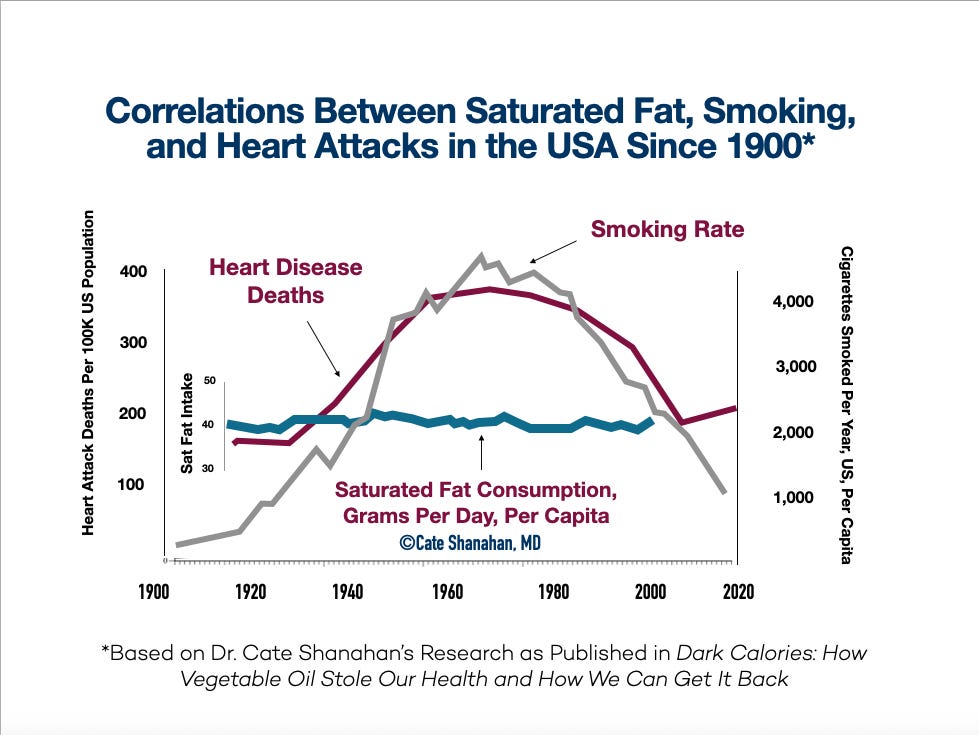

Some doctors noticed a trend: most of these men were heavy smokers, burning through two, three, even four packs a day. And now, with the benefit of hindsight, we can trace heart-attack and smoking rates throughout the 20th century and see that the two lines move almost perfectly together. Both rose through the first half of the century, peaked in the 1950s and ’60s, and then fell rapidly as smoking declined.

But back then, researchers only had the first part of the graph. Even though the early data implicated smoking, one man would tell the world a different story — a story that would change everything.

The Power of an Image

That man was Ancel Keys, a physiologist with a forceful personality and a gift for persuasion. Keys believed that America’s growing waistline was not just unhealthy, but immoral. In interviews, he lamented the nation’s “weak will” and the “disgusting sin” of weight gain, calling for a return to puritanical self-discipline.

His theory was simple: fat in the diet caused fat to build up in the arteries. He told Americans that when we eat butter, eggs, and meat, the cholesterol they contain slowly chokes off the flow of blood, clogging our arteries “like hot grease in a cold pipe.”

It was a powerful image — terrifying and easy to remember. But it was also utterly misleading, because our blood does not travel through metal pipes. Arteries are living tissues that expand, repair, and respond to injury. Cholesterol doesn’t damage our arteries. In fact, all evidence suggests the opposite, that the body places it there as a kind of biological waterproofing to prevent damaged coronary arteries from leaking or triggering clots, either of which could be fatal. Some researchers, myself included, believe that plaque is more like a scar than a disease process in itself.

But Keys’ metaphor was sticky. It spread faster than the truth ever could.

And that, right there, is where nutrition science lost its footing — where metaphor replaced reality and marketing overtook medicine.

Keys had a gift for selling his ideas. He persuaded the president of the American Heart Association (AHA), Dr. Paul Dudley White, to adopt his theory as the foundation of heart-disease prevention. The AHA had recently undergone an internal struggle. Some leaders wanted to partner with industry to accelerate research into the root cause of heart disease and beat out competing organizations. Others feared that industry influence would corrupt the science.

As often happens, money won out. In 1948, the AHA accepted a massive donation approved by Procter & Gamble (which just so happened to sell soy and cottonseed oils, both highly refined members of what I call the ‘Hateful Eight’ seed oils). Now, to achieve their ambition, they needed to at least appear to have a solution to the mystery of heart attacks.

Keys gave them that solution.

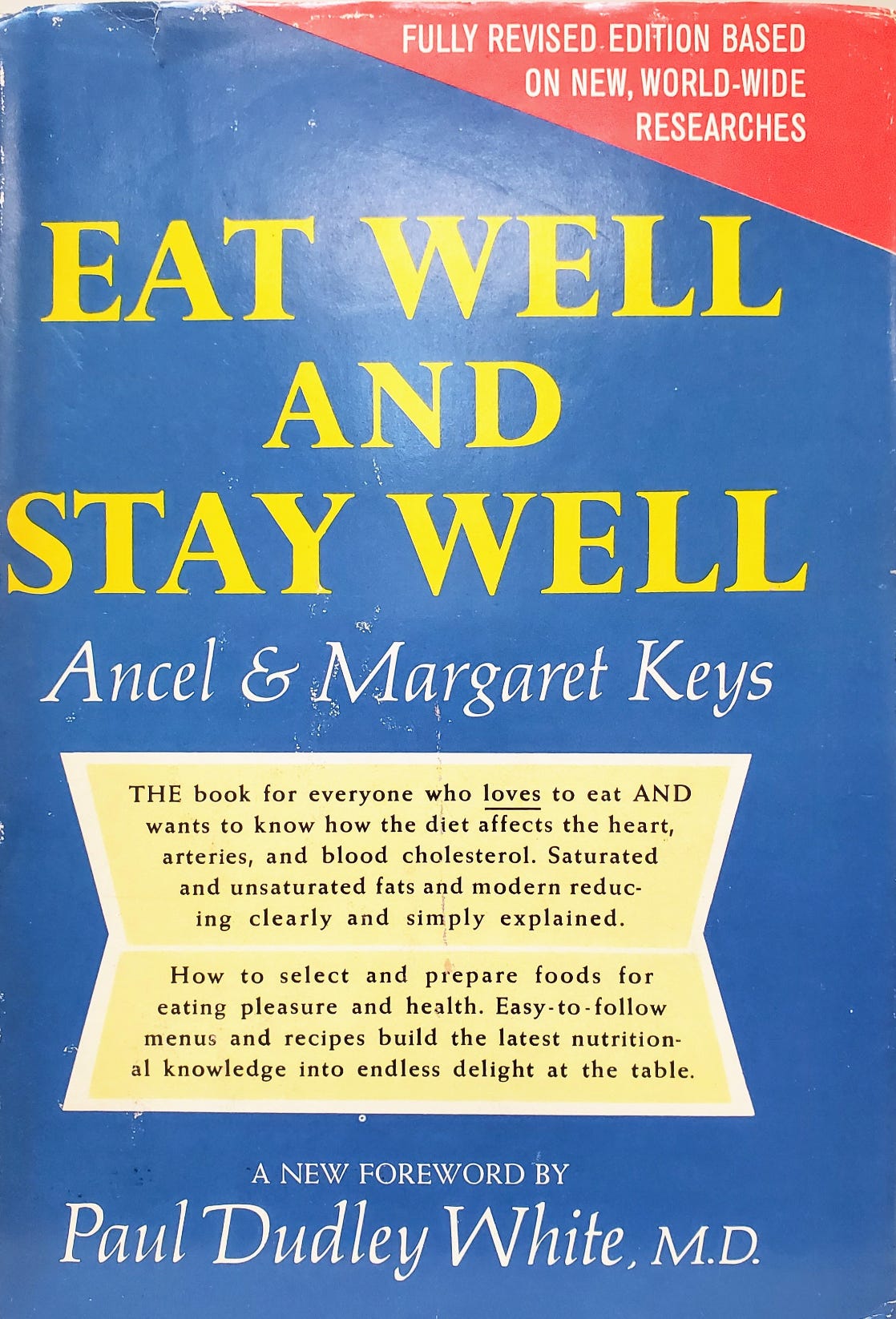

Soon, the AHA was promoting Keys’ theory linking cholesterol to heart disease. They endorsed his cholesterol-lowering cookbook, Eat Well and Stay Well, encouraging women to protect their husbands’ hearts by swapping butter and lard for “heart-healthy” plant oils like soy, cottonseed, and corn. Time Magazine put him on its cover in 1961, sealing his place in history.

Selling oils to consumers solved half the AHA’s problem. Solving the other half required bringing dietitians on board.

Why Dietitians Promote Seed Oils

The cholesterol theory created the perfect cover story for one of the most destructive industrial shifts in human history. If cholesterol itself was the problem, then anything that lowered it looked like a solution — even if it quietly poisoned us.

That’s where seed oils came in. When added to the diet, they lower cholesterol. On paper, that made them look “heart-healthy.” But what those numbers never revealed is how they do it. Seed oils oxidize the particles that carry cholesterol through our bloodstream, called lipoproteins. The liver clears these damaged particles, suffering oxidation in the process, so they disappear faster from the blood. The result looks like success on paper, but it’s biological chaos under the microscope.

The AHA managed to convince generations of doctors that cholesterol was a toxin to be eradicated, not a nutrient to be understood. And because medical training never touches on the intricacies of edible oil production, most dietitians still don’t know that industrial refining strips natural antioxidants from oils, leaving behind unstable fatty acids that oxidize easily into toxins.

These toxins aren’t additives — they’re created inside the oil itself during manufacturing, storage, and cooking. Because they’re not deliberately added, our food safety agencies don’t test for them. And because dietitians don’t learn how these oils are made, the healthcare system has no reason to believe such toxins exist. That’s why medicine continues to deny their existence, even as physicians confront the diseases these compounds cause every day.

The Path to Truth

For a few decades, heart attack deaths did fall, mostly because Americans quit smoking. But as seed-oil consumption kept climbing, heart disease began to rise again, especially among younger adults. The pattern is unmistakable.

This is the real heart disease epidemic: oxidative stress from industrial fats and processed foods. And it all traces back to a simple, seductive image — “hot grease in a cold pipe” — that replaced biology with marketing.

To fix this, the MAHA movement must go deeper into the scientific archives than any previous administration. Repairing public health means understanding the origin story of the cholesterol myth, and the seed oil empire, and that together these are two halves of the same illusion. It will require reeducating doctors to understand that healthy arteries aren’t empty pipes; they’re living tissues that depend, in part, on cholesterol.

The next generation of health-conscious consumers, doctors, and dietitians can do better. Indeed, they must do better, because our current seed oil intake is causing so much oxidative stress, I believe it threatens our survival as a species. To fix nutrition science, we need to question the comfort of “settled science,” and to learn what really happens when we process the fats that feed our cells.

That’s how we begin to heal — with the courage to see what’s been hiding in our blind spots all along.

Dr. Cate Shanahan, MD (DrCate.com) is The New York Times bestselling author of Deep Nutrition, Food Rules, The Fatburn Fix, and, most recently, Dark Calories. You can follow her on X @DrCateShanahan

I never bought into the egg/meat/butter lie, thank goodness. It may have been partly because I loved all three and was in denial, but I am glad in hindsight that I kept eating eggs my whole life (and quit cigarettes). The seed oils, though, are hard to avoid. They are often contained even in organic foods -- read your labels!!

Good stuff, Cate!